Napoleon Bonaparte: The Rise and Fall of a Revolutionary Emperor

Few historical figures have left as profound an impact on European history as Napoleon Bonaparte. From humble beginnings on the island of Corsica to becoming Emperor of France and conquering much of Europe, Napoleon’s meteoric rise and dramatic fall continue to fascinate historians and the public alike. His military genius, political reforms, and personal ambition transformed the landscape of Europe and established principles of governance that endure to this day. This article explores the remarkable Napoleon Bonaparte rise and fall, examining how a young artillery officer became one of history’s most consequential leaders before suffering a catastrophic downfall.

Early Life and Military Education

Napoleon Bonaparte as a young military officer before his rise to power

Born on August 15, 1769, in Ajaccio, Corsica, Napoleon Bonaparte came from a family of minor Corsican nobility. Just one year before his birth, France had acquired Corsica from the Republic of Genoa, making Napoleon technically French, though he would maintain his Corsican identity and accent throughout his early life. His father, Carlo Buonaparte, was a lawyer who secured royal patronage, enabling young Napoleon to receive a military education on the French mainland.

In January 1779, at just nine years old, Napoleon left Corsica for France to attend a religious school in Autun, where he struggled to improve his French. His native languages were Corsican and Italian, and he would speak French with a Corsican accent throughout his life. Later that year, he transferred to the military academy at Brienne-le-Château, where he faced bullying due to his accent, birthplace, and mannerisms.

Despite these challenges, Napoleon excelled in mathematics and developed a keen interest in history and geography. One instructor noted that he “has always been distinguished for his application in mathematics” and that “this boy would make an excellent sailor.” In September 1784, Napoleon was admitted to the prestigious École militaire in Paris, where he trained to become an artillery officer.

The École militaire in Paris where Napoleon received his formal military training

When his father died in February 1785, the family’s financial situation deteriorated, forcing Napoleon to complete the two-year course in just one year. He graduated in September 1785 and was commissioned as a second lieutenant in La Fère artillery regiment. This early period of struggle and determination would shape the ambitious character that would later conquer much of Europe.

Napoleon and the French Revolution

The French Revolution that began in 1789 created the chaotic conditions that would eventually allow Napoleon’s rise to power. While initially stationed in Valence and Auxonne, Napoleon spent considerable time on leave in Corsica, where his Corsican nationalism flourished. As revolutionary fervor spread across France, Napoleon found himself navigating the complex political landscape of the time.

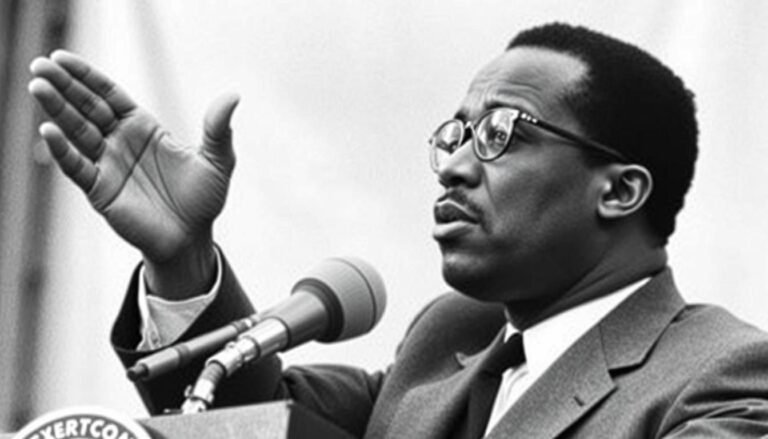

The tumultuous events of the French Revolution created opportunities for Napoleon’s advancement

In 1793, Napoleon demonstrated his military prowess during the Siege of Toulon, where he commanded republican artillery forces against British-occupied Toulon. His successful strategy to capture a hill fort that dominated the city’s harbor led to the recapture of the port and brought him to the attention of powerful figures in the revolutionary government, including Augustin Robespierre, brother of revolutionary leader Maximilien Robespierre.

Following this victory, Napoleon was promoted to brigadier general at the remarkably young age of 24. However, his association with the Robespierres became problematic after their fall from power in July 1794, leading to Napoleon’s brief arrest. Though released after two weeks, he found himself temporarily sidelined.

Napoleon’s fortunes changed dramatically on October 5, 1795 (13 Vendémiaire on the revolutionary calendar), when he helped suppress a royalist insurrection against the National Convention in Paris. Using “a whiff of grapeshot,” as Thomas Carlyle later described it, Napoleon’s decisive action in deploying artillery against the rebels earned him the patronage of the new government, the French Directory, and his appointment as commander of the Army of the Interior.

The Rise to Power: Military Genius and Political Ambition

The Italian Campaign and Egyptian Expedition

Napoleon’s Italian Campaign established his reputation as a military genius

In March 1796, Napoleon was appointed commander of the Army of Italy, marking the beginning of his meteoric rise. The Italian Campaign showcased Napoleon’s military genius, innovative tactics, and leadership abilities. In a series of swift victories during the Montenotte campaign, he defeated the Piedmontese forces in just two weeks before turning his attention to the Austrians.

Napoleon’s army captured 150,000 prisoners, 540 cannons, and 170 standards during this campaign. The French fought 67 actions and won 18 pitched battles through superior artillery technology and Napoleon’s tactical brilliance. Beyond military success, Napoleon extracted an estimated 45 million French pounds from Italy, along with precious metals, jewels, and over 300 priceless artworks.

Following his Italian triumphs, Napoleon led an ambitious expedition to Egypt in 1798, aiming to undermine British access to its trade interests in India. Though he won the Battle of the Pyramids against the Mamluks, the destruction of the French fleet by British Admiral Horatio Nelson at the Battle of the Nile stranded Napoleon’s forces. After a failed campaign in Syria, Napoleon abandoned his army in Egypt and returned to France in August 1799, sensing political opportunity amid the Directory’s growing unpopularity.

The Coup of 18 Brumaire

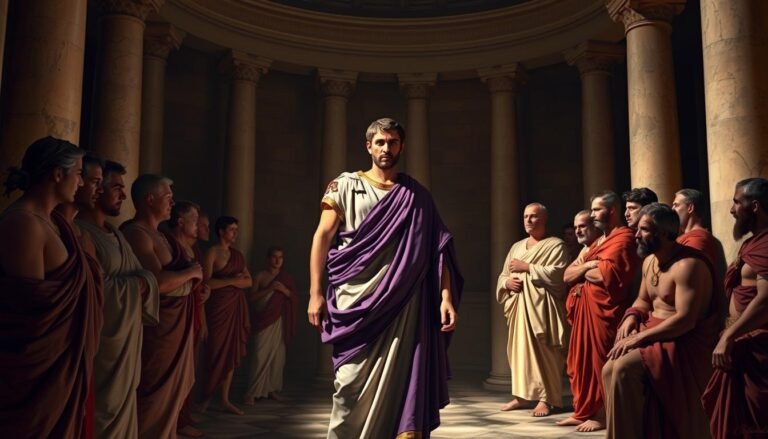

The Coup of 18 Brumaire established Napoleon as First Consul of France

Upon returning to France, Napoleon found the Directory weakened by military defeats and financial problems. Seizing this opportunity, he formed an alliance with Emmanuel Joseph Sieyès, Roger Ducos, and other influential figures to overthrow the government. On November 9, 1799 (18 Brumaire), Napoleon and his co-conspirators executed their coup d’état.

The following day, backed by grenadiers with fixed bayonets, they forced the Council of Five Hundred to dissolve the Directory and appoint Napoleon, Sieyès, and Ducos as provisional consuls. Within weeks, Napoleon had outmaneuvered his co-conspirators and established himself as First Consul with near-dictatorial powers.

“The revolution is over. I am the revolution.” — Napoleon Bonaparte after becoming First Consul

On December 15, 1799, Napoleon introduced the Constitution of the Year VIII, which established three consuls appointed for ten years. While Cambacérès and Charles-François Lebrun were named second and third consuls, real power resided with Napoleon as First Consul. The constitution was approved by a plebiscite in February 1800, with the official count showing over three million in favor and only 1,562 against—though Napoleon’s brother Lucien had doubled the “yes” votes to create the impression of overwhelming support.

Consolidation of Power and Domestic Reforms

The Napoleonic Code

The Napoleonic Code, one of Napoleon’s most enduring legacies

As First Consul and later Emperor, Napoleon implemented sweeping reforms that transformed French society and governance. His most significant and enduring achievement was the Napoleonic Code, a comprehensive legal framework that streamlined the French legal system. Introduced in 1804, the Code embodied Enlightenment principles of equality before the law, religious tolerance, and meritocracy while also reinforcing patriarchal authority within families.

The Napoleonic Code abolished feudal privileges, established property rights, and standardized legal procedures throughout France. It represented a compromise between revolutionary ideals and traditional values, preserving many of the social gains of the French Revolution while restoring order and stability. The Code’s influence extended far beyond France, serving as a model for legal systems throughout Europe and the Americas.

Key Reforms Under Napoleon’s Rule

- Establishment of the Bank of France (1800) to stabilize the economy

- Creation of the Legion of Honor (1802) to reward civilian and military achievements

- Concordat with Pope Pius VII (1801) reconciling the state with the Catholic Church

- Centralization of administration through the prefect system

- Reform of education with the creation of lycées and technical schools

- Development of infrastructure including roads, bridges, and canals

- Standardization of weights and measures using the metric system

From Republic to Empire

Napoleon crowning himself Emperor at Notre Dame Cathedral, December 2, 1804

Napoleon’s transformation from First Consul to Emperor marked the final abandonment of republican ideals. Following a royalist plot in 1804, Napoleon’s supporters convinced him that creating a hereditary regime would secure his position and make it more acceptable to European monarchies. On May 18, 1804, the Senate proclaimed Napoleon “Emperor of the French,” and a plebiscite in June confirmed this new title.

Napoleon’s coronation took place at Notre Dame Cathedral on December 2, 1804, with Pope Pius VII in attendance. In a dramatic gesture that symbolized his self-made authority, Napoleon took the crown from the Pope’s hands and placed it on his own head before crowning his wife Josephine as Empress. This act clearly demonstrated that Napoleon’s power derived not from divine right or papal blessing, but from his own achievements and the will of the French people.

As Emperor, Napoleon created a new nobility based on merit rather than birth, awarding titles to generals, officials, and supporters who had distinguished themselves in service to France. He established an elaborate imperial court with strict etiquette and ceremonial splendor, designed to rival the traditional monarchies of Europe. Yet despite these trappings of royalty, Napoleon continued to present himself as the heir to the Revolution, preserving its social gains while rejecting its political radicalism.

European Domination: The Napoleonic Wars

Military Innovations and Grand Strategy

Napoleon’s Grande Armée revolutionized warfare in Europe

Napoleon’s military genius transformed European warfare. He reorganized the French army into a flexible corps system that could march separately and fight together, allowing for unprecedented speed and maneuverability. The Grande Armée, created in 1805, initially comprised about 200,000 men organized into seven corps with artillery and cavalry reserves, plus the elite Imperial Guard. By August 1805, it had grown to 350,000 well-equipped and well-trained soldiers led by competent officers.

Napoleon’s preferred strategy involved rapid movement to divide enemy forces, concentrate his own troops at decisive points, and achieve local numerical superiority even when outnumbered overall. He emphasized offensive action, mobility, and the psychological impact of bold maneuvers. Napoleon personally commanded his armies, making quick decisions on the battlefield and inspiring his troops with his presence and proclamations.

“In war, the moral is to the physical as three is to one.”

The Height of Power: Austerlitz to Tilsit

The Battle of Austerlitz (December 2, 1805), often considered Napoleon’s greatest victory

The period from 1805 to 1807 marked the zenith of Napoleon’s military success. In the War of the Third Coalition, Napoleon achieved one of his greatest victories at the Battle of Austerlitz on December 2, 1805. Facing the combined armies of Austria and Russia, Napoleon deliberately weakened his right wing to entice the allies into attacking, then used his reserves to smash through their center and envelop their forces. The French inflicted 25,000 casualties while suffering only 9,000 of their own.

Following Austerlitz, Napoleon dissolved the Holy Roman Empire and created the Confederation of the Rhine, a collection of German states under French protection. In 1806, Prussia challenged French hegemony, leading to the War of the Fourth Coalition. At the twin battles of Jena and Auerstedt on October 14, 1806, Napoleon crushed the Prussian army, inflicting 25,000 casualties and capturing 18,000 prisoners.

Napoleon then turned east to confront Russia. After the bloody but inconclusive Battle of Eylau in February 1807, he decisively defeated the Russians at the Battle of Friedland on June 14, 1807. This victory led to the Treaties of Tilsit, in which Russia recognized French dominance in Western and Central Europe and joined the Continental System, Napoleon’s economic blockade against Britain.

The Continental System and European Reorganization

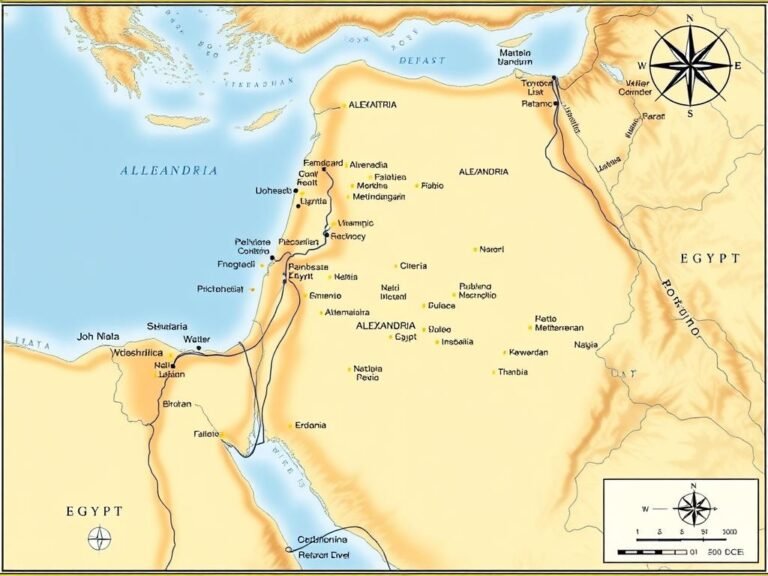

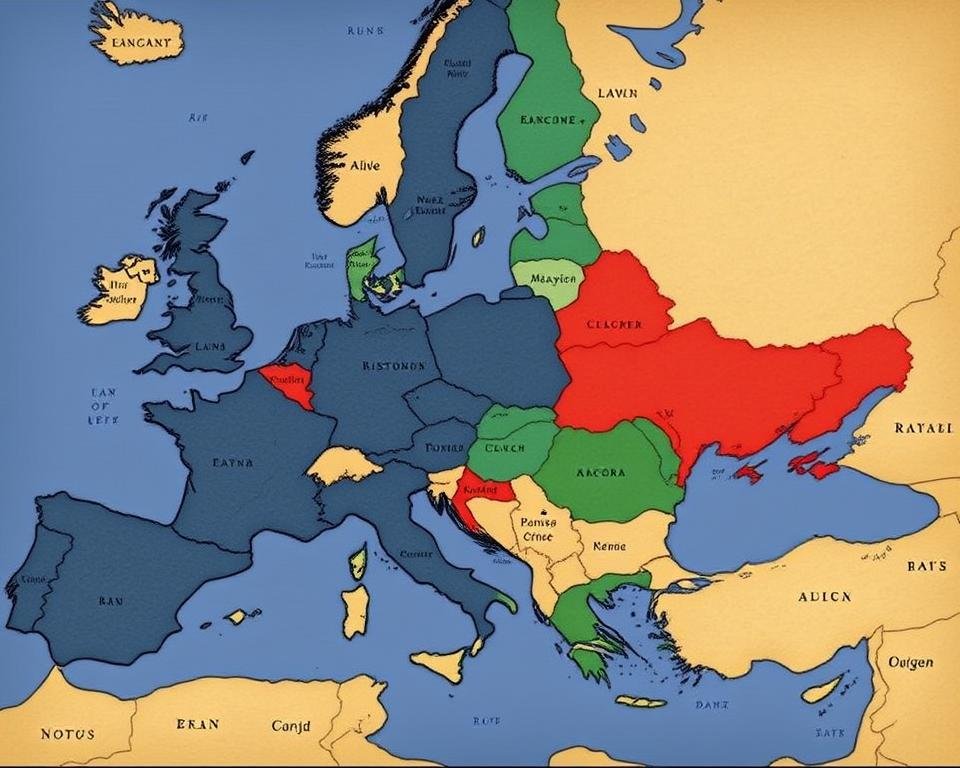

Map of Europe under Napoleon’s influence at its height

At the peak of his power, Napoleon controlled or influenced most of continental Europe. He reorganized the political landscape, placing family members on the thrones of several countries: his brother Joseph became King of Naples (later Spain), Louis became King of Holland, Jérôme ruled Westphalia, and his sister Caroline and brother-in-law Joachim Murat governed Naples after Joseph’s transfer to Spain.

The Continental System, established by the Berlin Decree of 1806, aimed to defeat Britain through economic warfare by prohibiting European nations from trading with the British. However, the blockade proved difficult to enforce, damaged the economies of France and its allies, and encouraged smuggling. Britain’s naval supremacy, secured at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805, allowed it to maintain its global trade networks despite Napoleon’s efforts.

Napoleon’s attempt to extend the Continental System to Portugal led to the Peninsular War (1808-1814), which became a costly drain on French resources. His decision to depose the Spanish Bourbons and install his brother Joseph as king provoked fierce resistance from the Spanish people, supported by British forces under Arthur Wellesley (later Duke of Wellington). The guerrilla warfare in Spain tied down hundreds of thousands of French troops and demonstrated the limits of Napoleon’s power.

The Beginning of the End: Overreach and Resistance

The Invasion of Russia

The catastrophic retreat from Moscow marked the beginning of Napoleon’s downfall

The invasion of Russia in 1812 marked the beginning of Napoleon’s downfall. Tensions between France and Russia had been growing since 1810, when Tsar Alexander I began allowing neutral shipping into Russian ports and banning most French imports, effectively withdrawing from the Continental System. Napoleon, viewing this as a threat to his European system, assembled the largest army Europe had ever seen—approximately 600,000 men from France and its allies—for the invasion.

On June 24, 1812, Napoleon’s Grande Armée crossed the Niemen River into Russian territory. Rather than engaging in a decisive battle, the Russians adopted a strategy of continuous retreat, drawing the French deeper into Russia while implementing a scorched earth policy that denied them supplies. The Russians finally made a stand at Borodino on September 7, resulting in a bloody battle with over 70,000 casualties on both sides.

Although the French technically won at Borodino, the Russian army retreated in good order, and Napoleon entered Moscow on September 14 only to find the city largely abandoned. The following night, fires broke out across Moscow, destroying much of the city and depriving the French of expected winter quarters. After waiting five weeks for a Russian surrender that never came, Napoleon began his disastrous retreat on October 19.

“The most terrible of all my battles was the one before Moscow. The French showed themselves worthy of victory, and the Russians worthy of being invincible.”

The retreat from Moscow turned into one of history’s most catastrophic military disasters. Harassed by Russian forces, suffering from starvation and the brutal Russian winter, the Grande Armée disintegrated. The crossing of the Berezina River in late November became particularly infamous, with thousands drowning or freezing to death. Of the approximately 600,000 men who began the campaign, only about 100,000 survived to return to friendly territory.

The War of Liberation

The Battle of Leipzig (1813), also known as the Battle of Nations, marked a decisive defeat for Napoleon

The Russian disaster emboldened Napoleon’s enemies. In early 1813, Prussia declared war on France, followed by Austria in August. The War of the Sixth Coalition saw Napoleon fighting against a united Europe. Despite initial victories at Lützen and Bautzen in May 1813, Napoleon’s depleted forces faced increasingly overwhelming odds.

The decisive Battle of Leipzig (October 16-19, 1813), also known as the Battle of Nations, involved over 600,000 troops, making it the largest battle in Europe prior to World War I. The coalition forces defeated Napoleon, inflicting 38,000 casualties and capturing 15,000 prisoners. This defeat forced the French to retreat across the Rhine, and by early 1814, coalition armies were advancing into France itself.

As the allies closed in on Paris, Napoleon conducted a brilliant defensive campaign with limited resources, but he could not overcome the coalition’s numerical superiority. When Paris fell on March 31, 1814, Napoleon’s marshals refused to continue fighting. On April 6, 1814, Napoleon abdicated unconditionally and was exiled to the Mediterranean island of Elba, while the Bourbon monarchy was restored in the person of Louis XVIII.

The Hundred Days and Final Defeat

Napoleon’s return from Elba began the brief period known as the Hundred Days

Napoleon’s first exile proved short-lived. Dissatisfaction with the restored Bourbon monarchy grew in France, while Napoleon, granted sovereignty over Elba, closely monitored events on the mainland. Learning that the allies were considering moving him to a more distant location and facing financial difficulties, Napoleon made a daring escape from Elba on February 26, 1815, with approximately 1,000 supporters.

Landing near Antibes on March 1, Napoleon began his march to Paris. Rather than facing resistance, he was greeted with increasing support. When troops were sent to arrest him near Grenoble, Napoleon approached them alone and declared, “Here I am. Kill your Emperor, if you wish!” Instead of firing, the soldiers shouted “Vive l’Empereur!” and joined his growing force. On March 20, Napoleon entered Paris triumphantly as King Louis XVIII fled to Belgium.

The European powers, still assembled at the Congress of Vienna, declared Napoleon an outlaw and pledged to field a combined force of 700,000 men to defeat him. Napoleon worked quickly to rebuild his army and implement liberal reforms to broaden his support, but he could only raise about 300,000 troops, many of them inexperienced.

The Battle of Waterloo

The Battle of Waterloo on June 18, 1815, ended Napoleon’s rule permanently

Deciding to strike before the coalition armies could unite, Napoleon led approximately 124,000 men into Belgium in June 1815, hoping to defeat the British and Prussian forces separately. After initial engagements at Ligny, where he defeated the Prussians, and Quatre Bras, Napoleon confronted the Duke of Wellington’s Anglo-Allied army at Waterloo on June 18, 1815.

The Battle of Waterloo became one of history’s most famous engagements. Wellington’s forces held defensive positions on a ridge, withstanding repeated French attacks throughout the day. Napoleon delayed his main assault until midday due to muddy ground from the previous night’s rain, giving the Prussian army under Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher crucial time to march to Wellington’s aid.

When Prussian forces arrived on Napoleon’s right flank late in the afternoon, the tide turned decisively against the French. Napoleon committed his elite Imperial Guard in a final desperate attack, but they were repulsed. As the Guard retreated, panic spread through the French army, and the battle ended in a rout. The French suffered approximately 25,000 casualties and 8,000 prisoners, while the allies lost about 22,000 men.

“The nearest run thing you ever saw in your life.”

Following this decisive defeat, Napoleon returned to Paris, where he found no support for continuing the fight. He abdicated for a second time on June 22, 1815, in favor of his son. After briefly considering escape to America, Napoleon surrendered to Captain Frederick Maitland of HMS Bellerophon on July 15. The British government, determined to prevent any further returns, exiled Napoleon to the remote South Atlantic island of Saint Helena, where he would spend the remaining six years of his life.

Exile to Saint Helena and Death

Longwood House on Saint Helena, where Napoleon spent his final years

Napoleon arrived at the island of Saint Helena in October 1815. Located 1,870 kilometers from the west coast of Africa, this remote British territory would be his home for the remaining years of his life. The British took extraordinary precautions to prevent any escape, stationing 2,100 soldiers on the island and maintaining a squadron of ships to patrol the surrounding waters.

Napoleon’s living conditions at Longwood House were far from the imperial splendor he had once enjoyed. The house was damp, windswept, and plagued by rats. Napoleon frequently complained about his treatment and living conditions in letters to the island’s governor, Hudson Lowe, with whom he had a contentious relationship. The British government’s harsh restrictions on Napoleon became controversial even in Britain, leading to parliamentary debates about his treatment.

Despite these circumstances, Napoleon maintained imperial formality, holding dinner parties where men wore military dress and women appeared in evening gowns. He spent his time dictating his memoirs and commentaries on military campaigns to his companions, particularly Emmanuel, comte de Las Cases. These dictations formed the basis of the “Memorial de Sainte Hélène,” which helped shape Napoleon’s historical legacy as he wished it to be remembered.

Napoleon during his exile on Saint Helena, where his health gradually deteriorated

Napoleon’s health began to deteriorate in 1817, with symptoms including swollen legs, abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. By early 1821, he was seriously ill and confined to bed. Napoleon died on May 5, 1821, at the age of 51. The official cause of death was recorded as stomach cancer, though some historians have suggested alternative theories, including arsenic poisoning.

In accordance with his wishes, Napoleon was buried on Saint Helena. However, in 1840, during the July Monarchy, King Louis-Philippe obtained British permission to return Napoleon’s remains to France. On December 15, 1840, Napoleon’s body was interred with great ceremony in a tomb at Les Invalides in Paris, where it remains today, a site of pilgrimage for admirers and a powerful symbol of French national identity.

“I wish my ashes to rest on the banks of the Seine, among the French people I have loved so much.”

The Legacy of Napoleon Bonaparte’s Rise and Fall

Napoleon’s tomb at Les Invalides in Paris remains a site of pilgrimage

Napoleon Bonaparte’s legacy is complex and contradictory, reflecting the multifaceted nature of his career and impact. As a military commander, he is widely regarded as one of history’s greatest generals. His innovative tactics, strategic vision, and leadership abilities transformed warfare and continue to be studied at military academies worldwide. The Napoleonic Wars reshaped the European continent and accelerated the development of modern nation-states.

As a statesman and reformer, Napoleon left an equally profound mark. The Napoleonic Code, with its principles of equality before the law, religious tolerance, and protection of private property, became a model for legal systems throughout Europe and beyond. His administrative reforms centralized and rationalized government, creating efficient bureaucracies that survived long after his fall. Educational reforms, including the establishment of lycées and technical schools, expanded access to education and promoted meritocracy.

Positive Legacies

- Modernization of legal systems through the Napoleonic Code

- Administrative efficiency and meritocratic principles

- Educational reforms and promotion of sciences

- Infrastructure development across Europe

- Emancipation of religious minorities in many territories

- Spread of revolutionary ideals beyond France

- Abolition of feudalism in conquered territories

Negative Legacies

- Millions of deaths in the Napoleonic Wars

- Reintroduction of slavery in French colonies

- Suppression of free press and political opposition

- Looting of conquered territories’ cultural treasures

- Establishment of authoritarian governance model

- Reduction of women’s rights under the Napoleonic Code

- Nationalist reactions that fueled later conflicts

Napoleon’s rise and fall also had profound cultural impacts. The Romantic movement in literature and art was partly inspired by his dramatic career. His image as the “great man” who shaped history through force of will influenced philosophers like Hegel and Nietzsche. The Napoleonic legend—carefully cultivated during his lifetime and enhanced by his memoirs—created an enduring mystique that has inspired countless books, films, and works of art.

Politically, Napoleon’s legacy is more ambiguous. While he preserved many of the French Revolution’s social gains, he abandoned its democratic principles in favor of authoritarian rule. His model of enlightened despotism influenced later leaders, for better and worse. The nationalism he inadvertently fostered through his conquests and the resistance they provoked would reshape European politics throughout the 19th and 20th centuries.

“Napoleon was as great as a man can be without virtue.”

Perhaps most significantly, Napoleon’s meteoric rise and dramatic fall embody timeless themes of ambition, genius, hubris, and nemesis. From humble origins on a small Mediterranean island, he rose to command an empire that spanned a continent, only to die in lonely exile on a remote Atlantic island. This narrative arc continues to fascinate and caution us about the possibilities and limitations of individual achievement and the corrupting nature of power.

Conclusion: Understanding the Napoleon Bonaparte Rise and Fall

The story of Napoleon Bonaparte’s rise and fall represents one of history’s most dramatic narratives of ascent to power and subsequent downfall. From his origins as a minor Corsican nobleman to becoming Emperor of the French and master of Europe, Napoleon’s journey exemplifies both the potential for individual achievement and the dangers of unchecked ambition.

Napoleon’s military genius, administrative talents, and personal charisma allowed him to seize opportunities created by the French Revolution and reshape Europe according to his vision. His legal, educational, and administrative reforms modernized France and influenced governance throughout Europe and beyond. Yet his insatiable ambition, inability to compromise, and strategic overreach ultimately led to his downfall.

The disastrous invasion of Russia in 1812 marked the beginning of the end, demonstrating the limits of military power against geography, climate, and determined resistance. The Battle of Waterloo in 1815 provided the final act in Napoleon’s political career, leading to his permanent exile on Saint Helena. Even in defeat and exile, however, Napoleon worked to shape his legacy through his memoirs and conversations, ensuring that future generations would remember him as he wished to be remembered.

Today, more than two centuries after his death, Napoleon Bonaparte remains a subject of fascination, debate, and study. His complex legacy continues to influence our understanding of leadership, governance, warfare, and the role of the individual in shaping history. The Napoleon Bonaparte rise and fall reminds us that even the most extraordinary individuals are subject to the constraints of their time, the limitations of human capability, and the consequences of their own choices.

Further Reading on Napoleon Bonaparte’s Rise and Fall

Napoleon: A Life

Andrew Roberts’ comprehensive biography draws on thousands of recently published letters to provide a nuanced portrait of Napoleon as military commander, emperor, and man.

The Campaigns of Napoleon

David G. Chandler’s classic work remains the definitive account of Napoleon’s military strategies, tactics, and battles, essential for understanding his rise to power and eventual defeat.

Napoleon: The Path to Power

Philip Dwyer’s first volume explores Napoleon’s early life and career, offering insights into the formation of his character and the political maneuvering that enabled his meteoric rise.

Frequently Asked Questions About Napoleon Bonaparte’s Rise and Fall

Was Napoleon Bonaparte really short?

Contrary to popular belief, Napoleon was not exceptionally short. He was approximately 5 feet 7 inches tall (1.7 meters), which was average height for a man of his time. The misconception about his height originated from British propaganda and confusion between French and English measurement systems. The French inch (pouce) was longer than the English inch, making his reported height of 5 feet 2 inches in French measurement equivalent to about 5 feet 7 inches in English measurement. Additionally, Napoleon was often surrounded by tall bodyguards, which may have made him appear shorter by comparison.

How did Napoleon rise to power so quickly?

Napoleon’s rapid rise to power resulted from a combination of factors: his exceptional military talent demonstrated during the Italian Campaign and in Egypt; the political instability of the French Directory, which created opportunities for a strong leader; his political acumen and ability to build alliances with influential figures like Talleyrand and Sieyès; and his popular appeal as a military hero. The Coup of 18 Brumaire in 1799 was the culmination of these factors, allowing him to seize power and establish himself as First Consul before eventually becoming Emperor.

What were the main causes of Napoleon’s downfall?

Napoleon’s downfall can be attributed to several key factors: the disastrous invasion of Russia in 1812, which decimated his Grande Armée; the continuous drain of resources from the Peninsular War in Spain; Britain’s naval supremacy and economic warfare; the growing nationalism in occupied territories that fueled resistance; the formation of increasingly powerful coalitions against France; and Napoleon’s own strategic overreach and inability to accept compromise. His insistence on total victory rather than negotiated peace, particularly after the Russian campaign, ultimately led to his defeat and exile.

What is the Napoleonic Code and why is it important?

The Napoleonic Code (Code Civil des Français) is a comprehensive legal framework introduced in 1804 that remains the foundation of French civil law and has influenced legal systems worldwide. Its importance lies in its codification of revolutionary principles like equality before the law, freedom of religion, and abolition of feudal privileges, while also establishing clear rules for property rights, contracts, and family law. The Code represented a compromise between revolutionary ideals and traditional values, and its clarity and systematic organization made it a model for legal reform throughout Europe and former French colonies.

How did Napoleon die and was he poisoned?

Napoleon died on May 5, 1821, on the island of Saint Helena. The official cause of death was stomach cancer, which was also the cause of his father’s death. However, controversy has surrounded his death, with some theories suggesting arsenic poisoning. Analysis of Napoleon’s hair samples has shown high levels of arsenic, but this may be explained by environmental factors such as arsenic in wallpaper dyes or medicines rather than deliberate poisoning. Most historians and medical experts now accept stomach cancer as the most likely cause, consistent with his reported symptoms and family medical history.

References and Further Resources

- Roberts, Andrew. (2014). Napoleon: A Life. Penguin Books.

- Chandler, David G. (1966). The Campaigns of Napoleon. Scribner.

- Dwyer, Philip. (2008). Napoleon: The Path to Power. Yale University Press.

- Zamoyski, Adam. (2018). Napoleon: A Life. Basic Books.

- Englund, Steven. (2004). Napoleon: A Political Life. Harvard University Press.

- Schom, Alan. (1997). Napoleon Bonaparte. HarperCollins.

- McLynn, Frank. (1997). Napoleon: A Biography. Arcade Publishing.

- Cronin, Vincent. (1971). Napoleon. HarperCollins.