Julius Caesar: From Hero to Betrayal – The Tragic Arc of Rome’s Most Controversial Leader

Few historical figures have left a legacy as enduring as Julius Caesar. His name remains synonymous with power, ambition, and betrayal more than two millennia after his death. The dramatic arc of Caesar’s life – from brilliant military commander to controversial dictator to the victim of history’s most famous assassination – continues to captivate our imagination and offers timeless lessons about leadership, power, and loyalty.

Caesar’s rise to unprecedented power through military conquest and popular reforms ultimately collided with the Roman Republic’s traditional power structures. This tension between innovation and tradition, between one man’s vision and the established order, culminated in the ultimate betrayal on the Ides of March, 44 BCE, when Caesar was stabbed 23 times by men he considered allies and friends. This article explores how the seeds of betrayal were sown throughout Caesar’s meteoric rise and how his assassination, rather than preserving the Republic, accelerated its transformation into an empire.

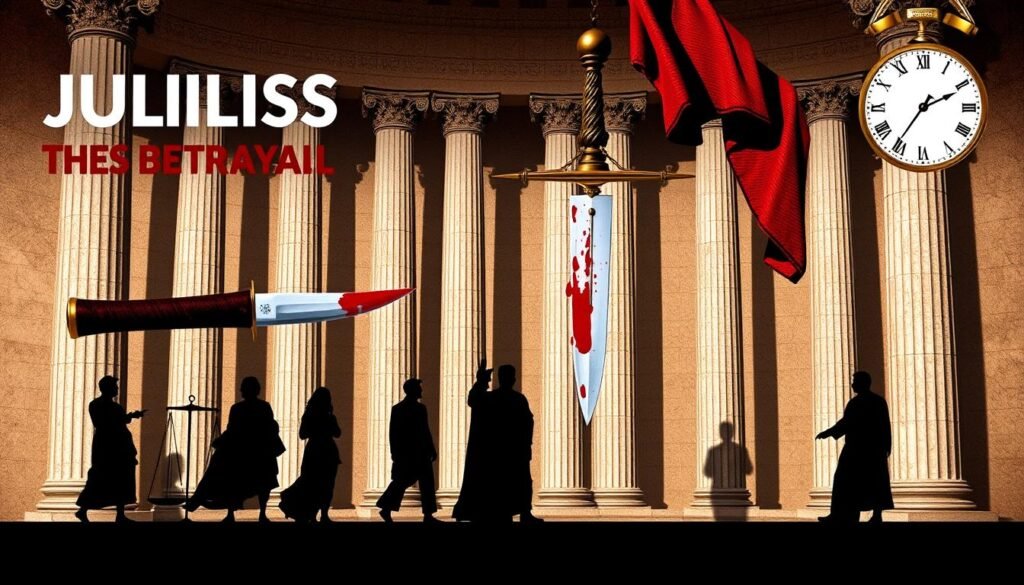

The final moments before Julius Caesar’s betrayal in the Roman Senate, a pivotal moment that changed the course of history.

The Rise of a Hero: Caesar’s Path to Power

Julius Caesar’s ascent to power began with his extraordinary military campaigns. His conquest of Gaul (modern-day France and parts of Belgium) between 58-50 BCE demonstrated not only his tactical brilliance but also his ability to inspire loyalty among his troops. Caesar’s military innovations transformed the Roman army into a more efficient fighting force, with improved weapons, tactics, and a revolutionary command structure that rewarded merit over social status.

In his own words from his Commentaries on the Gallic War, Caesar described his achievements: “All Gaul is divided into three parts… I came, I saw, I conquered.” These weren’t merely boasts but reflections of a commander who expanded Rome’s territory by nearly a third and brought immense wealth into Roman coffers.

Caesar’s military genius during the Gallic Wars established his reputation and built his power base.

Populist Reforms and Public Adoration

Beyond the battlefield, Caesar positioned himself as a champion of the common people. His populist reforms included land redistribution to veterans and the urban poor, debt relief measures, and the famous Julian calendar reform that rationalized the Roman calendar system (a version of which we still use today). These measures earned him tremendous popularity among the masses while simultaneously stoking resentment among the elite.

Plutarch notes in his Lives that “Caesar won the love and ardent devotion of the masses by the magnificence of his shows, his feasts, and his gifts.” This public adoration provided Caesar with a power base independent of the traditional aristocratic support structures, further threatening the established order.

“The people would have it so,” Caesar reportedly said when implementing reforms against senatorial opposition, highlighting his populist approach to governance.

Elite Resentment Grows

While the common people celebrated Caesar’s rise, the Roman elite watched with growing alarm. His military successes made him dangerously popular with the army. His reforms undermined their economic privileges. Most concerning of all, his accumulation of titles and honors seemed to be trending toward monarchy – a system Romans had proudly rejected nearly five centuries earlier.

The tension between public adoration and elite resentment created the volatile political environment that would eventually lead to Caesar’s downfall. As his power grew, so too did the determination of those who saw him as a threat to the Republic’s very existence.

Caesar’s Popular Reforms

- Land redistribution to veterans and the poor

- Grain subsidies for Roman citizens

- Debt relief and interest rate regulations

- Julian calendar reform (365.25 days)

- Expansion of Roman citizenship

- Infrastructure projects throughout Rome

Sources of Elite Opposition

- Fear of losing traditional privileges

- Concerns about Caesar’s growing power

- Resentment of his populist policies

- Alarm at his accumulation of titles

- Suspicion of monarchical ambitions

- Personal rivalries and jealousies

Seeds of Betrayal: Power, Fear, and Conspiracy

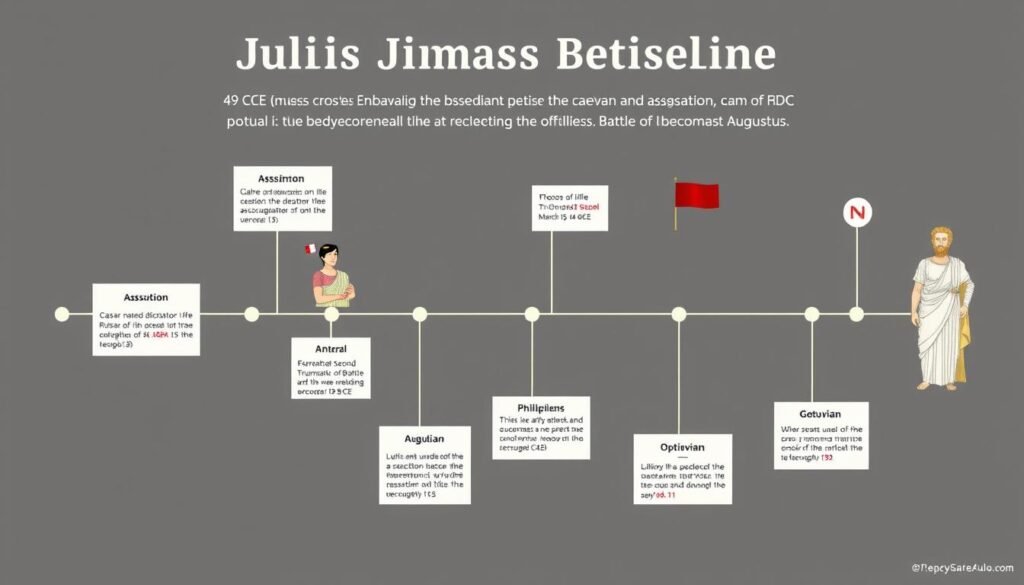

The seeds of Julius Caesar’s betrayal were planted in the soil of his own success. By 44 BCE, Caesar had accumulated unprecedented power in the Roman Republic. After defeating his rival Pompey and the republican forces, he was appointed dictator – initially for ten years, but in February 44 BCE, he was named “dictator perpetuo” (dictator for life). This permanent dictatorship crossed a critical line for many Romans.

Caesar’s appointment as dictator perpetuo (dictator for life) alarmed many Romans who feared the return of monarchy.

Power Consolidation: The Dictator for Life

Caesar’s consolidation of power manifested in various ways that alarmed traditionalists. He placed his own image on Roman coins – previously reserved for gods and abstract representations. He accepted extraordinary honors, including a golden throne in the Senate, the right to wear triumphal clothing, and public statues depicting him with godlike attributes. While Caesar may have seen these as appropriate recognition of his achievements, to many Romans they evoked the trappings of monarchy.

According to the historian Suetonius, when Caesar was offered a crown by Mark Antony at the Lupercalia festival in February 44 BCE, he refused it – but many believed his refusal was merely for show. The incident heightened fears that Caesar intended to make himself king in all but name.

The Senate’s Fears: Republic in Peril

For the Roman elite, particularly senators from old aristocratic families, Caesar represented an existential threat to the Republic. The Roman Republic had been founded in 509 BCE specifically to overthrow monarchy, and its political system was designed with checks and balances to prevent any one individual from gaining too much power.

Caesar’s actions – dismissing tribunes who opposed him, appointing his own supporters to key positions, and governing increasingly without meaningful consultation – suggested to many that the Republic’s days were numbered. As Cicero would later write, “When arms speak, the laws fall silent.” The fear that Caesar was dismantling republican institutions drove many otherwise moderate senators toward radical action.

“Men willingly believe what they wish to believe.” — Julius Caesar

Key Figures: Brutus, Cassius, and Their Motivations

At the center of the conspiracy against Caesar were Marcus Junius Brutus and Gaius Cassius Longinus. Their motivations reveal the complex personal and political dimensions of the betrayal. Brutus, in particular, embodied this complexity. As a descendant of Lucius Junius Brutus, who had helped overthrow Rome’s last king, he felt a familial duty to protect the Republic. Yet Caesar had shown him extraordinary favor, pardoning him after he fought for Pompey and appointing him to high office.

Plutarch writes that Brutus was torn between gratitude to Caesar and duty to Rome: “Brutus could be caught by the honor, Cassius by the profit.” Cassius, more pragmatic and perhaps more personally resentful of Caesar, became the driving force behind the conspiracy, convincing Brutus that they acted not out of personal hatred but patriotic duty.

Marcus Junius Brutus, whose personal conflict between loyalty to Caesar and duty to the Republic made him the most famous betrayer in history.

Together, they recruited approximately 60 conspirators, many of whom had personal grievances against Caesar or ideological commitments to the Republic. Their plan was not merely to remove Caesar from power but to restore what they saw as proper republican governance – a goal that would prove far more difficult than the assassination itself.

The Ides of March: Betrayal Unleashed

The date chosen for Caesar’s assassination – March 15, 44 BCE, known to Romans as the Ides of March – would become forever synonymous with betrayal. According to Plutarch and Suetonius, Caesar had been warned by a soothsayer to “beware the Ides of March.” On the morning of his assassination, his wife Calpurnia begged him not to attend the Senate meeting, having dreamed of his murder. Yet Caesar, either dismissing these warnings or unwilling to show fear, proceeded to the Theatre of Pompey where the Senate was temporarily meeting.

“Cowards die many times before their deaths; The valiant never taste of death but once.”

The Dramatic Assassination Scene

The scene that unfolded in the Senate chamber that day has been dramatized countless times, most famously in Shakespeare’s play, but the historical accounts are no less dramatic. As Caesar took his seat, the conspirators gathered around him, ostensibly to present a petition. Tillius Cimber approached first, pulling at Caesar’s toga as a signal to the others. When Caesar irritably tried to push him away, Casca struck the first blow with his dagger, shouting “Brothers, help!”

What followed was a frenzied attack as the conspirators surrounded Caesar, drawing their hidden daggers. Caesar initially fought back, even wounding one attacker with his stylus. But when he saw Brutus among the assassins, he reportedly uttered the famous words, “You too, my child?” (in Greek, “Kai su, teknon?”), covered his face with his toga, and resigned himself to his fate.

The assassination of Julius Caesar, where he received 23 stab wounds from men he considered allies and friends.

The conspirators stabbed Caesar 23 times, though according to the physician Antistius, only one wound (the second one to his chest) was fatal. In their frenzy, some conspirators even wounded each other. When it was over, Caesar lay dead at the foot of a statue of his former rival, Pompey – a detail rich with historical irony.

Immediate Aftermath: Chaos in Rome

The immediate aftermath of the assassination was not what the conspirators had expected. Rather than being hailed as liberators who had saved the Republic, they found themselves in a dangerous and chaotic situation. The senators who had not been part of the conspiracy fled the chamber in panic. The assassins, their togas stained with blood, marched to the Capitol, proclaiming they had freed Rome from a tyrant.

But the Roman people did not rally to their cause. Instead, a sense of shock and uncertainty prevailed. Mark Antony, Caesar’s loyal lieutenant and co-consul, went into hiding, fearing he might be the next target. Brutus addressed the crowd, attempting to justify the assassination as a necessary act to preserve liberty, but his abstract appeals to republican principles failed to resonate with ordinary citizens who had benefited from Caesar’s populist policies.

The Turning Point: Mark Antony’s Funeral Oration

The conspirators made a critical mistake in allowing Mark Antony to speak at Caesar’s funeral. In a masterful display of rhetoric, Antony turned public opinion against the assassins while appearing to praise them:

“For Brutus is an honorable man; So are they all, all honorable men…” His ironic repetition of “honorable men” while displaying Caesar’s bloodied toga and reading his will (which left generous gifts to the Roman people) inflamed the crowd against the conspirators.

The public reaction to Caesar’s funeral marked a decisive turning point. The crowd, moved to fury by Antony’s speech and the sight of Caesar’s mutilated body, rioted through the streets. They used benches and tables to build a funeral pyre in the Forum, cremating Caesar’s body on the spot rather than in the planned location. The conspirators, now fearing for their lives, fled Rome.

What had begun as a calculated political assassination intended to restore the Republic had instead plunged Rome into a new period of instability and conflict. The betrayal of Julius Caesar, far from solving Rome’s political crisis, had only deepened it.

Legacy of the Betrayal: Unintended Consequences

The assassination of Julius Caesar stands as one of history’s great ironies: an act intended to save the Roman Republic instead ensured its demise. The conspirators who plunged their daggers into Caesar on the Ides of March believed they were preventing one man’s tyranny, but they inadvertently paved the way for an imperial system that would last for centuries.

How the Act Backfired: The End of the Republic

In the power vacuum that followed Caesar’s death, three men emerged to claim his legacy: Mark Antony (Caesar’s loyal lieutenant), Lepidus (Caesar’s Master of Horse), and Octavian (Caesar’s adopted son and heir). Together they formed the Second Triumvirate, ostensibly to restore order but effectively to divide power among themselves.

Their first act was to systematically eliminate their enemies through proscriptions – published lists of “enemies of the state” who could be killed on sight, their property confiscated. Many senators, including the famed orator Cicero, perished in this purge. The triumvirs then turned their attention to hunting down Caesar’s assassins.

The Battle of Philippi (42 BCE), where the forces of Antony and Octavian defeated Brutus and Cassius, sealing the fate of Caesar’s assassins and the Republic.

At the Battle of Philippi in 42 BCE, the forces of Brutus and Cassius were defeated by those of Antony and Octavian. Both conspirators committed suicide rather than face capture. As Brutus reportedly said before taking his life: “Caesar, now be still: I killed not thee with half so good a will.” With their deaths, the republican cause lost its most prominent champions.

The triumvirate itself proved unstable. After eliminating Lepidus from power and defeating Antony at the Battle of Actium, Octavian emerged as the sole ruler of Rome. In 27 BCE, he was granted the title “Augustus” by the Senate and became Rome’s first emperor, though he carefully maintained republican facades while wielding monarchical power. The Republic that Brutus and Cassius had killed Caesar to preserve was gone forever.

“How many ages hence shall this our lofty scene be acted over in states unborn and accents yet unknown!”

Modern Parallels: Leadership, Power, and Loyalty

The betrayal of Julius Caesar continues to resonate because it encapsulates timeless themes about leadership, power, and loyalty that remain relevant today. The tension between effective leadership and democratic principles, between necessary change and traditional values, between personal loyalty and civic duty – these conflicts are as present in modern politics as they were in ancient Rome.

Caesar’s assassination raises profound questions that still challenge us: When does reform become revolution? When does strong leadership become tyranny? When is resistance justified? When does loyalty to principles outweigh loyalty to individuals? These questions have no simple answers, which is why the story of Caesar’s betrayal continues to fascinate and instruct.

Historical Impact of Caesar’s Assassination

- Triggered civil war and proscriptions

- Led to the formation of the Second Triumvirate

- Resulted in the defeat and death of the conspirators

- Accelerated the transition from Republic to Empire

- Established precedent for political violence

- Created the conditions for Augustus’ rise to power

Caesar’s Enduring Legacy

- Military reforms that transformed Roman warfare

- Julian calendar that influenced modern timekeeping

- Expansion of Roman citizenship and territory

- Literary works that set standards for Latin prose

- Political centralization that shaped imperial governance

- Cultural symbol of leadership and betrayal

Perhaps the most profound legacy of Caesar’s betrayal is how it demonstrates that history rarely follows the intentions of those who try to shape it. The conspirators who killed Caesar to prevent one-man rule instead created the conditions for the very system they opposed. As the historian Tacitus would later observe about the transition from Republic to Empire: “They would have neither absolute slavery nor absolute freedom.”

Augustus Caesar (Octavian), who emerged from the chaos following Julius Caesar’s assassination to become Rome’s first emperor, effectively ending the Republic the conspirators had sought to preserve.

Conclusion: The Eternal Lessons of Caesar’s Betrayal

The betrayal of Julius Caesar represents one of history’s great cautionary tales. It reminds us that political violence, even when motivated by noble ideals, often produces consequences far different from those intended. The conspirators who struck down Caesar in the name of liberty inadvertently ushered in an imperial age that would last for centuries.

Caesar’s story also illuminates the eternal tension between change and tradition, between strong leadership and institutional constraints. Caesar was a brilliant innovator who recognized Rome’s need for reform, but his methods threatened the very foundations of the Republic. His assassins were defenders of tradition who failed to recognize that the old order they cherished had already become unsustainable.

Perhaps most poignantly, the betrayal of Julius Caesar reveals the complex interplay between personal relationships and political principles. Brutus, torn between his friendship with Caesar and his duty to Rome, embodies this conflict. His decision to prioritize what he saw as the greater good over personal loyalty has made him a symbol of both principled sacrifice and the darkest betrayal.

“The evil that men do lives after them; The good is oft interred with their bones.”

More than two thousand years after his death, Julius Caesar’s legacy endures – not just in history books but in our cultural understanding of power, leadership, and betrayal. His name has become synonymous with both greatness and the price it sometimes exacts. The Ides of March remains a powerful reminder that even the mightiest can fall when they lose the trust of those closest to them.

The betrayal of Julius Caesar continues to influence our understanding of power, loyalty, and political change in the modern world.

Explore the World of Ancient Rome

Delve deeper into the fascinating history of Julius Caesar, the Roman Republic, and the rise of the Empire through our premium documentary collection. Understand the complex political machinations, military campaigns, and social changes that shaped this pivotal era in human history.

Further Reading on Julius Caesar’s Betrayal

Primary Sources

- Plutarch’s Parallel Lives (Life of Caesar)

- Suetonius’ The Twelve Caesars

- Cassius Dio’s Roman History

- Cicero’s Letters and Philippics

- Caesar’s own Commentaries

Modern Scholarship

- Adrian Goldsworthy’s Caesar: Life of a Colossus

- Barry Strauss’ The Death of Caesar

- Mary Beard’s SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome

- Tom Holland’s Rubicon

- Christian Meier’s Caesar: A Biography

Literary Interpretations

- Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar

- Thornton Wilder’s The Ides of March

- Colleen McCullough’s Masters of Rome series

- Robert Harris’ Dictator

- Conn Iggulden’s Emperor series

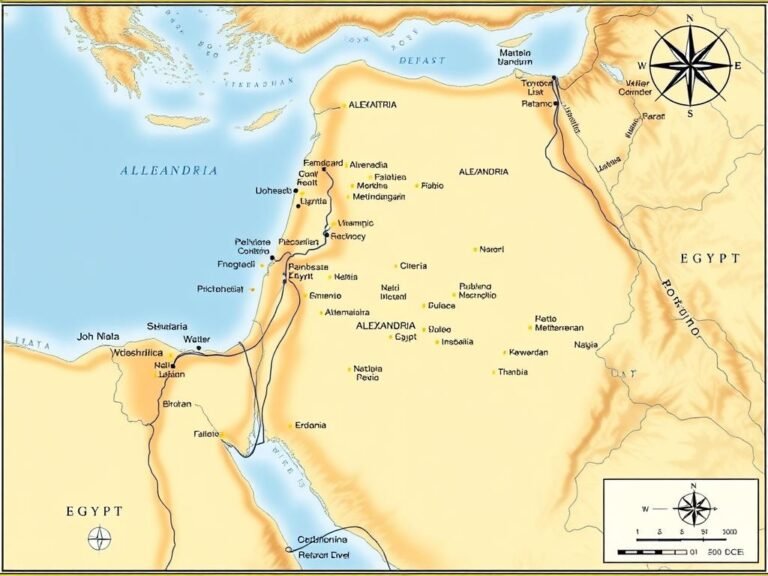

Timeline of key events surrounding Julius Caesar’s betrayal and its aftermath, showing how the assassination led to the fall of the Republic and rise of the Empire.