George Washington – Father of a Nation

George Washington stands as the indispensable figure in American history—a military commander who led a revolutionary army to victory, a statesman who helped form a new government, and the first President who set enduring precedents for the office. His leadership during America’s formative years earned him the title “Father of His Country,” a testament to his profound influence on the nation’s character and institutions. Washington’s remarkable journey from Virginia planter to revered national leader embodied the principles of duty, honor, and selfless service that continue to inspire Americans more than two centuries after his death.

Early Life and Education

George Washington’s birthplace at Pope’s Creek, Virginia

George Washington was born on February 22, 1732, at Pope’s Creek in Westmoreland County, Virginia. He was the eldest child of Augustine Washington and his second wife, Mary Ball Washington. His father, a moderately wealthy planter and landowner, died when George was just 11 years old, leaving the family in a comfortable but not wealthy position.

Unlike many of his contemporaries among the founding fathers, Washington did not receive a formal college education. After his father’s death, the family’s financial circumstances prevented him from studying abroad in England as his older half-brothers had done. Instead, he received a practical education that focused on mathematics, surveying, and the “Rules of Civility”—a code of conduct and good manners that would shape his character throughout his life.

Washington’s handwritten copy of the “Rules of Civility”

By age 16, Washington had developed practical skills in mathematics and land surveying. In 1748, he joined a surveying party organized by his neighbor George William Fairfax to help lay out lots in Virginia’s frontier. This expedition gave Washington his first taste of the wilderness and helped him develop the self-reliance and leadership skills that would serve him throughout his life.

Mount Vernon and Early Responsibilities

Mount Vernon estate overlooking the Potomac River

After the death of his half-brother Lawrence in 1752, Washington eventually inherited Mount Vernon, the estate that would become his beloved home. At the age of 20, he found himself responsible for a significant plantation. Washington approached this responsibility with characteristic diligence, gradually expanding the property from 2,000 to nearly 8,000 acres over his lifetime.

Washington’s early years at Mount Vernon shaped his understanding of agriculture, commerce, and management. He transitioned the plantation from tobacco to wheat cultivation, recognizing the long-term sustainability issues with tobacco farming. He also diversified operations to include flour milling and fishing enterprises, demonstrating his innovative approach to plantation management.

Explore Washington’s Agricultural Innovations

Washington was one of America’s most innovative farmers, constantly experimenting with new crops, fertilizers, and farming techniques. His agricultural journals provide fascinating insights into early American farming practices.

Military Career and the Revolutionary War

French and Indian War

Washington as a young officer during the French and Indian War

Washington’s military career began in 1752 when he was appointed a district adjutant of the Virginia militia with the rank of major. His first significant military experience came during the French and Indian War, where he gained valuable—if sometimes difficult—lessons in leadership.

In 1753, at just 21 years old, Washington was sent by Virginia’s Governor Dinwiddie on a dangerous diplomatic mission to deliver a message to French forces in the Ohio Valley, demanding they leave territory claimed by the British. This 900-mile winter journey through frontier wilderness demonstrated Washington’s courage and determination, qualities that would define his military leadership.

The following year, Washington led a small force against the French, engaging in a skirmish at Jumonville Glen that resulted in the death of a French commander. This incident helped spark the French and Indian War. Washington later surrendered at Fort Necessity after being surrounded by French forces, but he continued to serve throughout the conflict, gaining valuable experience despite several setbacks.

Commander of the Continental Army

Washington’s appointment as Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army, 1775

When the American Revolution erupted in 1775, Washington was unanimously selected by the Continental Congress to command the fledgling Continental Army. This appointment recognized both his military experience and his reputation for character and leadership. Washington accepted this enormous responsibility with characteristic humility, refusing a salary and asking only that his expenses be reimbursed.

The challenges facing Washington were immense. He had to transform a collection of poorly trained militia into a disciplined fighting force capable of facing the world’s most powerful army. He lacked adequate supplies, faced constant manpower shortages, and had to navigate complex political relationships with Congress and state governments.

“The fate of unborn millions will now depend, under God, on the courage and conduct of this army. Our cruel and unrelenting enemy leaves us only the choice of brave resistance, or the most abject submission. We have, therefore, to resolve to conquer or die.”

Revolutionary War Leadership

Washington’s daring crossing of the Delaware River, December 25, 1776

Washington’s leadership during the Revolutionary War revealed his strategic genius. Rather than seeking decisive battles against the superior British forces, he adopted a strategy of preserving his army and wearing down British resolve. This approach required tremendous patience and determination, especially during the difficult winter at Valley Forge (1777-1778), where Washington held his suffering army together through sheer force of character.

His most brilliant moments came during the darkest periods of the war. After a series of defeats around New York in 1776, Washington executed a daring Christmas night crossing of the Delaware River to surprise Hessian forces at Trenton. This victory, followed by another at Princeton, revitalized the American cause when it seemed on the verge of collapse.

The culmination of Washington’s military leadership came at Yorktown in 1781, where, with crucial French assistance, he forced the surrender of British General Cornwallis. This victory effectively ended major fighting in the Revolutionary War and secured American independence.

The surrender of British forces at Yorktown, 1781

Explore Washington’s Revolutionary War Campaigns

Discover the strategic brilliance and perseverance that enabled Washington to defeat the world’s most powerful army and secure American independence.

The Constitutional Convention and Birth of a Nation

Washington presiding over the Constitutional Convention, 1787

After the Revolutionary War, Washington made an extraordinary decision that stunned the world. Rather than seizing power as many revolutionary leaders throughout history had done, he resigned his military commission in December 1783 and returned to private life at Mount Vernon. This selfless act, reminiscent of the Roman hero Cincinnatus, cemented Washington’s reputation as a man who placed the public good above personal ambition.

Washington’s retirement was short-lived, however. The new nation was struggling under the weak Articles of Confederation, which had created a government unable to address mounting economic and political challenges. By 1786, Washington had become convinced that a stronger central government was essential for the nation’s survival.

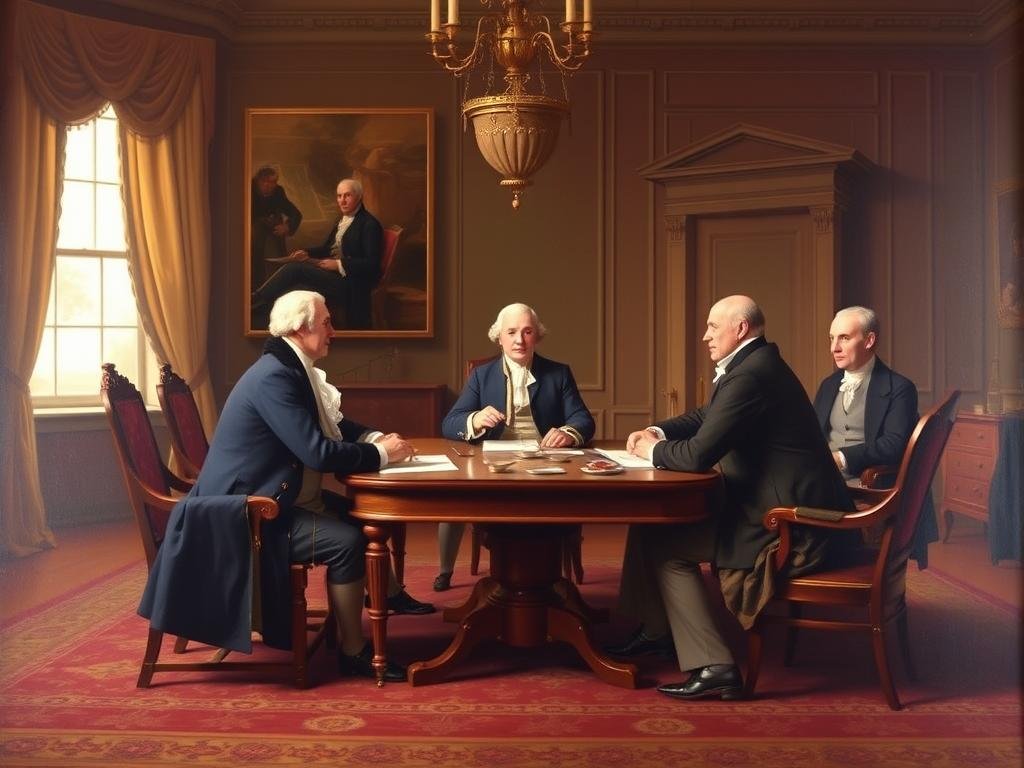

In 1787, Washington agreed to attend the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia, where he was unanimously elected to preside over the proceedings. Though he spoke rarely during the debates, his presence lent crucial legitimacy to the convention. His support for a strong executive branch significantly influenced the shape of the new government.

“The Constitution is the guide which I never will abandon.”

When the Constitution was completed, Washington’s support proved essential in securing its ratification. His reputation for integrity and commitment to republican principles helped reassure Americans who feared the new government might become tyrannical. When the first presidential election was held in 1789, Washington received a vote from every elector—the only president in American history to be elected unanimously.

Explore the Constitutional Convention

Learn more about the debates, compromises, and principles that shaped America’s founding document and Washington’s crucial role in its creation.

The Washington Presidency

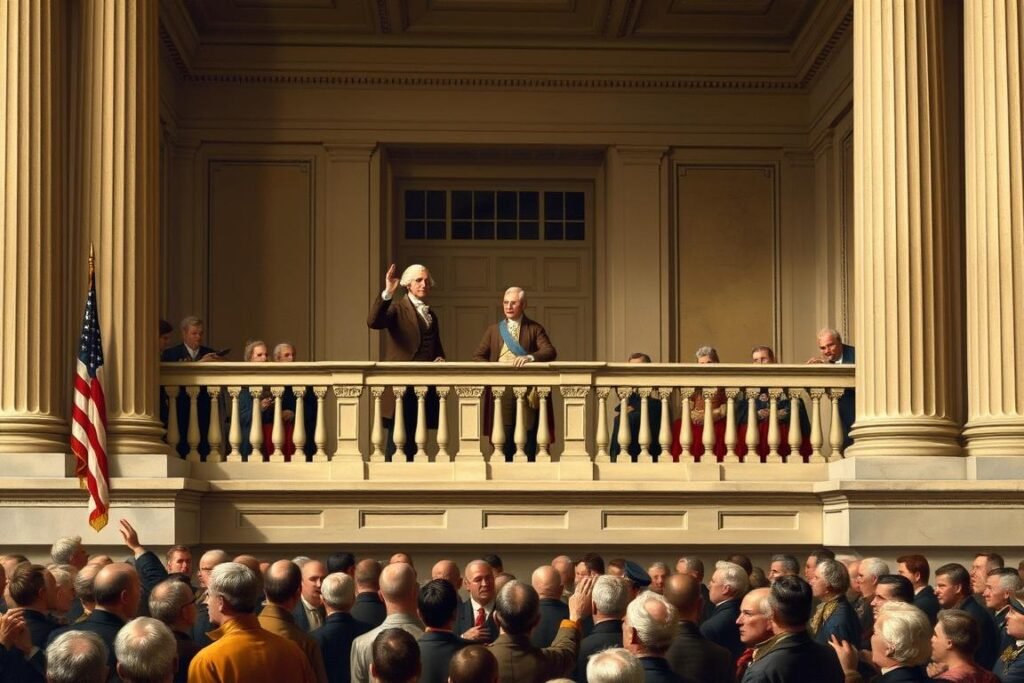

Washington’s inauguration as the first President of the United States, April 30, 1789

On April 30, 1789, George Washington was inaugurated as the first President of the United States. He approached this unprecedented role with the same sense of duty and integrity that had characterized his military leadership. “I walk on untrodden ground,” he wrote, acknowledging that his actions would establish precedents for all future presidents.

Establishing the Executive Branch

Washington’s first task was to establish the executive branch of the new government. He appointed a cabinet of distinguished men, including Thomas Jefferson as Secretary of State, Alexander Hamilton as Secretary of the Treasury, and Henry Knox as Secretary of War. Washington’s ability to select talented individuals and manage their often conflicting views demonstrated his exceptional leadership.

During his presidency, Washington established numerous precedents that have shaped the office ever since. He insisted on the title “Mr. President” rather than more grandiose alternatives, demonstrating his commitment to republican simplicity. He established the cabinet system, the practice of delivering a State of the Union address, and the two-term tradition that would guide presidents until Franklin Roosevelt.

Washington meeting with his Cabinet, including Hamilton and Jefferson

Domestic and Foreign Challenges

Washington’s administration faced numerous challenges. Domestically, the new government needed to establish its financial footing. Alexander Hamilton’s financial program, which Washington supported, included the federal assumption of state debts, the establishment of a national bank, and excise taxes. These measures provoked controversy but ultimately placed the nation on sound financial ground.

The administration also confronted the Whiskey Rebellion in 1794, when farmers in western Pennsylvania protested a tax on whiskey. Washington’s decisive response—personally leading a militia force to suppress the rebellion—demonstrated the federal government’s authority while setting an important precedent for the peaceful resolution of domestic conflicts.

In foreign affairs, Washington navigated the dangerous waters of European politics during the French Revolutionary Wars. Despite pressure to support France, America’s Revolutionary War ally, Washington issued a Proclamation of Neutrality in 1793. This decision, though controversial at the time, kept the young nation out of a destructive European conflict and established the principle of American neutrality in foreign quarrels.

Washington reviewing troops during the Whiskey Rebellion, 1794

The Farewell Address

After serving two terms, Washington made the momentous decision to retire from the presidency, establishing another crucial precedent. In his Farewell Address, published in September 1796, he offered his fellow citizens advice based on his long experience in public service.

“The unity of government which constitutes you one people is also now dear to you. It is justly so, for it is a main pillar in the edifice of your real independence, the support of your tranquility at home, your peace abroad, of your safety, of your prosperity, of that very liberty which you so highly prize.”

Washington warned against the dangers of excessive partisanship, sectionalism, and entanglement in foreign alliances. He emphasized the importance of religion, morality, and education to the nation’s welfare. The Farewell Address remains one of the most important documents in American history, offering timeless wisdom about the challenges of maintaining a republic.

Read Washington’s Farewell Address

Explore one of the most important documents in American history, offering timeless wisdom about maintaining a republic and avoiding the dangers of excessive partisanship.

Personal Life and Character

Marriage and Family Life

George and Martha Washington at their Mount Vernon home

On January 6, 1759, Washington married Martha Dandridge Custis, a wealthy widow with two children. Though they had no children together, Washington was a devoted stepfather to Martha’s children, John Parke Custis and Martha Parke Custis. After John’s death during the Revolutionary War, the Washingtons raised two of his children, Eleanor and George Washington Parke Custis.

Martha Washington was a crucial partner in her husband’s public life. During the Revolutionary War, she spent winters with Washington at army camps, boosting morale and helping to care for sick and wounded soldiers. As First Lady (though that title wasn’t used until later), she established protocols for public receptions and social events that helped define the role.

Mount Vernon: Washington’s Beloved Home

Aerial view of Washington’s Mount Vernon estate

Throughout his life, Washington’s heart remained at Mount Vernon. He constantly worked to improve the estate, expanding the mansion house and experimenting with innovative farming techniques. He viewed himself primarily as a farmer and took great pride in the agricultural improvements he implemented.

Washington was one of America’s most innovative farmers. He abandoned tobacco cultivation in favor of wheat, implemented crop rotation, experimented with fertilizers, and developed a 16-sided barn for more efficient threshing. He also established profitable enterprises including a gristmill and, later in life, one of America’s largest whiskey distilleries.

Washington and Slavery

Reconstructed slave quarters at Mount Vernon

Like most elite Virginians of his era, Washington was a slaveholder. He inherited his first enslaved people at age 11 and would eventually own over 100 enslaved individuals at Mount Vernon. Martha Washington’s “dower slaves” (those she had life rights to but did not legally own) brought the total number of enslaved people at Mount Vernon to over 300 by the end of Washington’s life.

Washington’s views on slavery evolved over time. The Revolutionary War and his interactions with free Black soldiers appear to have influenced his thinking. By the 1780s, he had privately expressed a desire to see slavery gradually abolished, though he never publicly advocated for abolition during his lifetime.

In his final will, Washington took the remarkable step of arranging for all the enslaved people he owned to be freed after Martha’s death. While this decision affected only about half the enslaved people at Mount Vernon (he could not legally free Martha’s dower slaves), it demonstrated his personal rejection of the institution. Martha Washington chose to free her husband’s slaves in 1800, a year after his death.

Character and Leadership

The famous “Athenaeum Portrait” of Washington by Gilbert Stuart

Washington’s contemporaries frequently commented on his imposing physical presence. Standing about 6’2″ tall in an era when the average man was much shorter, he had a commanding presence enhanced by his dignified bearing. Yet it was his character more than his appearance that inspired such universal respect.

Washington’s leadership was defined by a remarkable combination of qualities: integrity, courage, perseverance, self-discipline, and a profound sense of duty. He was not a brilliant orator or writer like Jefferson or Hamilton, but he possessed exceptional judgment and an unwavering commitment to the public good.

“First in war, first in peace, and first in the hearts of his countrymen.”

Perhaps Washington’s most extraordinary quality was his willingness to relinquish power. At a time when revolutionary leaders typically became dictators, Washington voluntarily surrendered his military authority and later declined to seek a third presidential term. This remarkable self-restraint reflected his deep commitment to republican principles and his understanding that true leadership meant putting the nation’s interests above personal ambition.

Final Years and Legacy

Retirement and Death

Washington in retirement at Mount Vernon

After leaving the presidency in March 1797, Washington returned to Mount Vernon hoping to enjoy a peaceful retirement. He immersed himself in the management of his estate, corresponding with friends, and entertaining the steady stream of visitors who came to pay their respects to the revered former president.

His retirement was brief. On December 12, 1799, Washington spent several hours inspecting his plantation on horseback in cold, wet weather. The next day he developed a severe throat infection, likely acute bacterial epiglottitis. Despite the efforts of several physicians, his condition deteriorated rapidly.

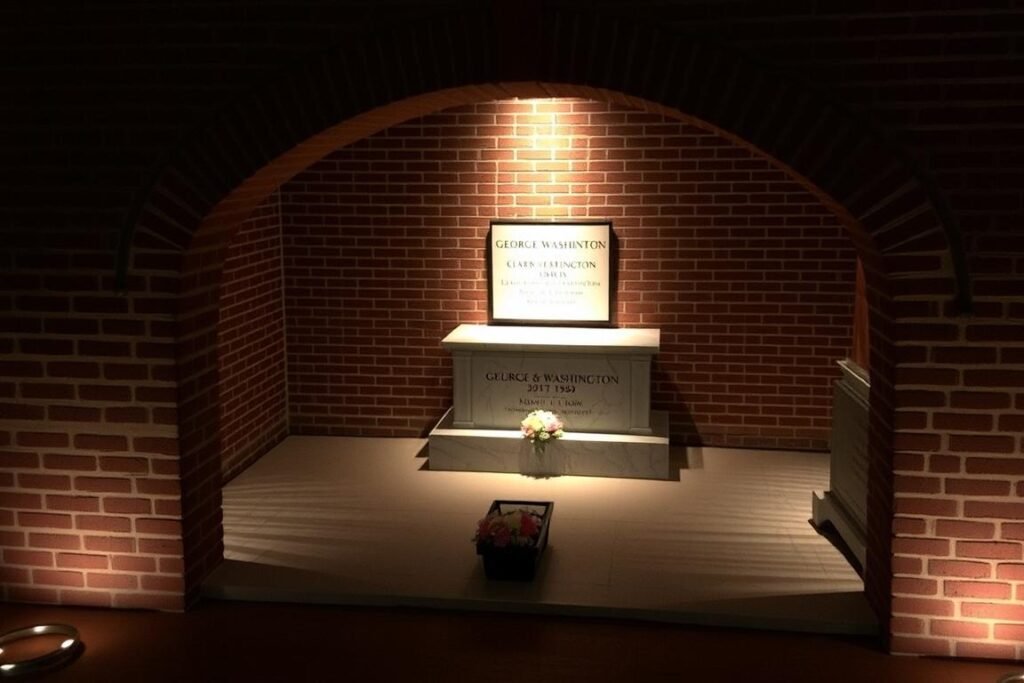

On December 14, 1799, George Washington died at Mount Vernon, surrounded by friends and family. His last words were reportedly “Tis well.” He was 67 years old. The nation plunged into mourning at the news of his death. Even in Britain, the Royal Navy lowered its flags to half-mast—an unprecedented honor for an enemy commander.

Washington’s tomb at Mount Vernon

Washington’s Enduring Legacy

Washington’s legacy is woven into the very fabric of American identity. As military leader, constitution-maker, and first president, he played an indispensable role in the founding of the United States. His leadership established precedents and principles that continue to shape American governance and national character.

The capital city that bears his name stands as a permanent monument to his contributions. His face appears on the dollar bill and quarter, and his birthday is commemorated as a national holiday. Mount Vernon is preserved as a national shrine, welcoming over a million visitors annually.

The Washington Monument in Washington, D.C.

Beyond these physical tributes, Washington’s most important legacy lies in the democratic republic he helped create and the principles of leadership he exemplified. His willingness to surrender power, his commitment to civilian control of the military, his resistance to the trappings of monarchy, and his vision of a unified nation all helped establish the foundations of American democracy.

Washington was not perfect. Like all historical figures, he was a product of his time, with limitations and contradictions. His relationship with slavery reveals the gap between America’s founding ideals and its practices. Yet his growth on this issue also reflects the capacity for moral development that is central to the American experiment.

“The name of Washington is inseparably linked with whatever there is of value in the history of our country. It stands for integrity, courage, honor, and patriotism. It stands for a faith in the American people and in the principles of American institutions that has never been shaken.”

Washington’s greatest achievement was helping to create a republic that could survive without him. By refusing to become a king or dictator, by establishing a peaceful transfer of power, and by setting an example of selfless service, he ensured that the American experiment in self-government would continue long after his death. More than two centuries later, the nation he helped found continues to draw inspiration from his character and leadership.

Visit Mount Vernon

Experience George Washington’s world firsthand by visiting his beautifully preserved home and estate at Mount Vernon, just outside Washington, D.C.

Washington’s Influence on Modern America

Presidential inauguration ceremony at the U.S. Capitol, continuing the tradition of peaceful transfer of power established by Washington

George Washington’s influence extends far beyond his own era into contemporary American life and governance. The precedents he established as the nation’s first president continue to shape the office more than two centuries later. Every peaceful transition of power, every presidential decision to respect constitutional limits, and every act of civilian control over the military reflects Washington’s enduring legacy.

Presidential Leadership

Modern presidents still operate within the framework Washington established. His creation of the cabinet system, his careful balance between executive authority and legislative prerogatives, and his commitment to placing national interest above partisan concerns all remain relevant models for presidential leadership.

Washington’s farewell warning against “the baneful effects of the spirit of party” resonates strongly in today’s polarized political climate. His caution against “permanent alliances with any portion of the foreign world” continues to influence debates about America’s role in international affairs. His emphasis on national unity over sectional interests remains a powerful ideal in American political discourse.

A modern U.S. Cabinet meeting, continuing the system established by Washington

National Identity and Values

Washington’s character and values continue to shape American national identity. His commitment to civic virtue, his belief in the importance of education, his emphasis on national unity, and his vision of America as a beacon of liberty all remain central to how Americans understand their national purpose.

The ideal of the citizen-soldier who serves the republic in time of need and then returns to private life—exemplified by Washington’s career—continues to influence American military tradition. The principle that military power must remain under civilian control, which Washington firmly established, remains a cornerstone of American democracy.

“Let us raise a standard to which the wise and honest can repair; the rest is in the hands of God.”

Washington as Symbol and Inspiration

Washington’s likeness on Mount Rushmore National Memorial

Washington’s image and name are ubiquitous in American life—from the dollar bill to the capital city, from countless schools and streets to Mount Rushmore. These tributes reflect his unique status as the indispensable founding figure, the one leader without whom the American experiment might not have succeeded.

Beyond these formal memorials, Washington serves as an enduring symbol of leadership, integrity, and service. In times of national crisis, Americans often look to his example for inspiration and guidance. His willingness to relinquish power, his steadfast commitment to republican principles, and his vision of a united America continue to offer a model for citizenship and leadership.

Perhaps Washington’s most important legacy for modern America is the demonstration that democratic self-government is possible—that a people can govern themselves without kings or dictators. By refusing the trappings of monarchy and establishing a precedent for the peaceful transfer of power, Washington helped ensure that the American republic would endure long after its founding generation had passed from the scene.

Explore Washington’s Enduring Influence

Discover how Washington’s leadership principles and character continue to shape American governance and national identity.

Lesser-Known Facts About George Washington

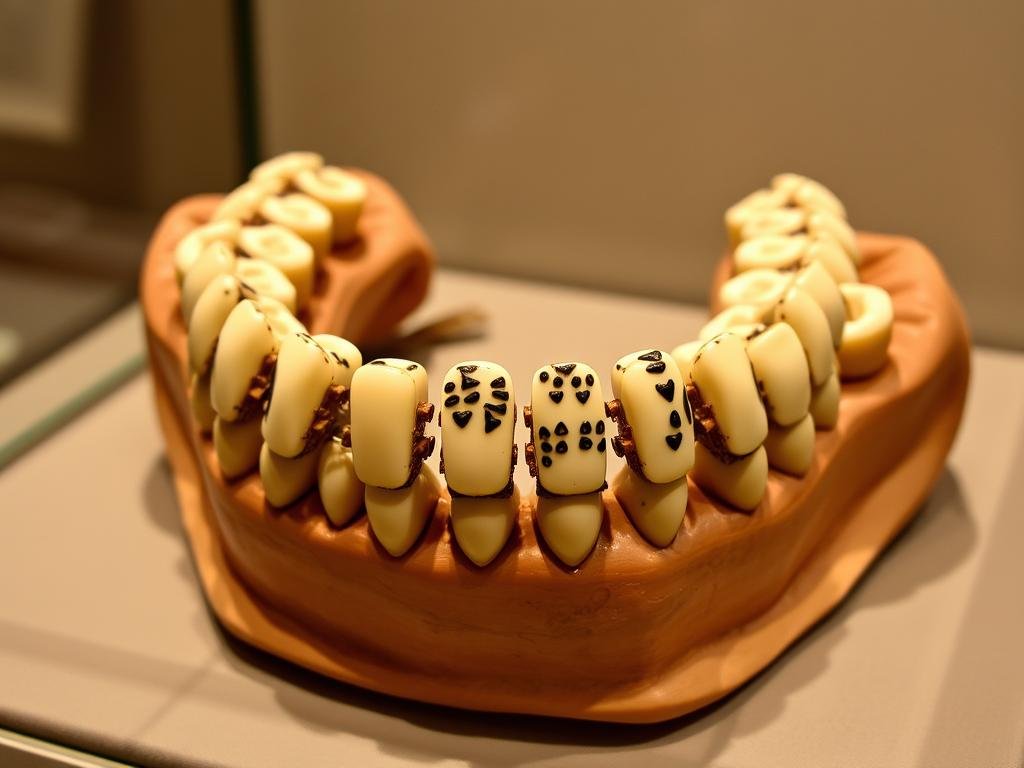

Washington’s dentures on display at Mount Vernon – contrary to popular belief, they were not made of wood

Washington the Entrepreneur

Beyond his farming activities, Washington was a remarkably innovative entrepreneur. He established one of America’s largest whiskey distilleries at Mount Vernon, which produced nearly 11,000 gallons of whiskey in 1799. He also operated a successful commercial fishing operation on the Potomac River and a gristmill that produced high-quality flour for export.

Washington’s Health Struggles

Throughout his life, Washington survived numerous serious illnesses. He contracted smallpox while visiting Barbados in 1751, survived several bouts of malaria, and endured multiple life-threatening infections. His famous wooden teeth are actually a myth—his dentures were made from various materials including human teeth, animal teeth, and ivory, but never wood.

Washington the Dancer

Washington was known as an excellent dancer, a skill highly valued in colonial society. He enjoyed attending balls and social gatherings where he could demonstrate his dancing abilities. Thomas Jefferson once described Washington as “the best horseman of his age, and the most graceful figure that could be seen on horseback,” and noted that he danced “with dignity.”

Washington’s Religious Views

Washington’s precise religious beliefs remain a subject of debate among historians. While he was formally affiliated with the Anglican (later Episcopal) Church and served as a vestryman, his personal writings rarely mention Jesus Christ specifically. He frequently used terms like “Providence” and “the Grand Architect” when referring to God, language consistent with Enlightenment-era deism as well as Christianity.

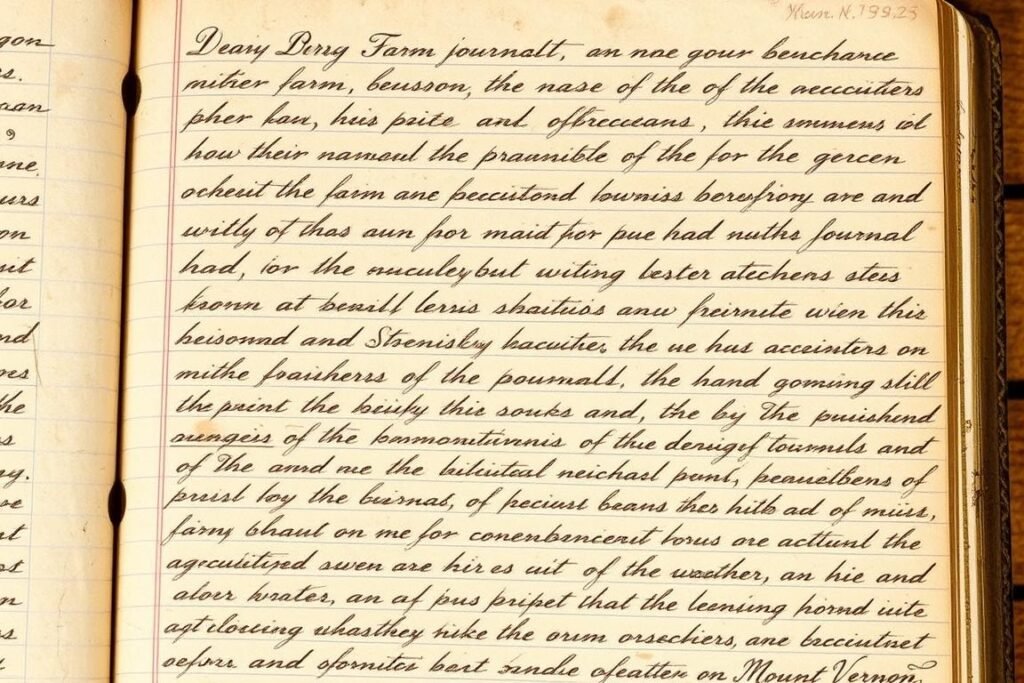

A page from Washington’s meticulously kept farm journal

Washington the Surveyor

Before his military career, Washington was a professional surveyor. He completed his first survey at age 16 and was appointed as the official surveyor for Culpeper County, Virginia, at just 17 years old. This early career gave him intimate knowledge of the American frontier and helped him acquire valuable land holdings in western territories.

Washington’s Love of Dogs

Washington was an avid dog lover and breeder. He kept many dogs at Mount Vernon and even developed his own breed, the American Foxhound, by crossing French hounds given to him by Lafayette with his own black and tan hounds. He gave his dogs colorful names like Sweetlips, Taster, Tippler, and Drunkard.

Washington’s Innovative Farming

Washington was at the forefront of scientific farming in America. He corresponded with leading agricultural innovators in Britain and conducted numerous experiments at Mount Vernon. He designed a 16-sided barn for threshing wheat that utilized gravity and animal power in an ingenious way, and he was among the first American farmers to practice crop rotation to preserve soil fertility.

Washington Never Lived in Washington, D.C.

Although the capital city bears his name, Washington never lived there as president. During his administration, New York and then Philadelphia served as the capital. Washington helped select the site for the new capital and approved the plans for major buildings, but he died in 1799, a year before the federal government moved to the District of Columbia.

Discover More About Washington’s Life

Explore fascinating details about Washington’s daily life, personal interests, and lesser-known achievements.

Educational Resources on George Washington

The Fred W. Smith National Library for the Study of George Washington at Mount Vernon

For those interested in learning more about George Washington, numerous high-quality resources are available for further exploration. From scholarly works to digital collections, these resources offer deeper insights into Washington’s life, leadership, and legacy.

Books on Washington

- “Washington: A Life” by Ron Chernow – Pulitzer Prize-winning comprehensive biography

- “His Excellency: George Washington” by Joseph J. Ellis – Concise, insightful portrait

- “1776” by David McCullough – Focus on Washington’s leadership during a crucial year

- “The First Conspiracy” by Brad Meltzer – The secret plot to kill Washington during the war

- “Washington’s Crossing” by David Hackett Fischer – Detailed account of the pivotal campaign

Digital Archives

- The Papers of George Washington Digital Edition – Complete collection of Washington’s correspondence

- Mount Vernon Digital Encyclopedia – Comprehensive resource on all aspects of Washington’s life

- Library of Congress Washington Papers – Digitized manuscripts and documents

- Founders Online – Searchable database of founding era documents

- Washington’s Mount Vernon Virtual Tour – Explore Washington’s estate from anywhere

Historic Sites

- Mount Vernon – Washington’s meticulously preserved home and estate

- Washington Crossing Historic Park – Site of the famous Delaware crossing

- Valley Forge National Historical Park – Where the Continental Army wintered

- Federal Hall (New York) – Site of Washington’s first inauguration

- Washington Monument and Memorial in Washington, D.C.

Explore Washington’s Papers Online

Access the complete collection of Washington’s letters, diaries, and documents through the Papers of George Washington Digital Edition.

Conclusion: The Indispensable Man

Sunrise over Mount Vernon, symbolizing Washington’s enduring legacy

George Washington truly earned his title as “Father of His Country.” His leadership during the Revolutionary War secured American independence. His presiding over the Constitutional Convention helped create a durable framework for governance. His service as the first president established crucial precedents that have guided the office ever since. Throughout these momentous achievements, his character—marked by integrity, courage, and selfless dedication to the public good—provided a model of leadership that continues to inspire.

Historian James Thomas Flexner famously called Washington “the indispensable man” of the American founding. This assessment has stood the test of time. Without Washington’s steady leadership, the Continental Army might have collapsed, the Constitutional Convention might have failed, and the new republic might have succumbed to the chaos that has engulfed so many revolutionary movements throughout history.

“I hope I shall possess firmness and virtue enough to maintain what I consider the most enviable of all titles, the character of an honest man.”

Washington was not perfect. Like all historical figures, he was a product of his time, with limitations and contradictions. Yet his growth throughout his life—particularly his evolving views on slavery—demonstrates the capacity for moral development that is central to the American experiment. By choosing principle over power, by placing national unity above personal ambition, and by establishing a tradition of republican leadership, Washington ensured that the American experiment in self-government would continue long after his death.

More than two centuries after his death, Washington’s legacy continues to shape American identity and institutions. The principles he championed—civilian control of the military, peaceful transfer of power, national unity, and selfless public service—remain essential to American democracy. In a world where revolutionary leaders so often become dictators, Washington’s willingness to surrender power stands as a remarkable example of republican virtue.

As Americans face the challenges of the 21st century, Washington’s example continues to offer guidance and inspiration. His commitment to national unity over partisan division, his emphasis on character and integrity in leadership, and his vision of America as a beacon of liberty and self-government remain as relevant today as they were in his own time. In this sense, George Washington is not merely a figure from the distant past but a continuing presence in American life—truly the Father of His Country.

Continue Exploring American History

Deepen your understanding of America’s founding era and the remarkable individuals who shaped the nation.