Diego Maradona: Football’s Fallen Angel – From Glory to Tragedy

This article explores the meteoric rise, chaotic downfall, and enduring legacy of Diego Armando Maradona – a man who lived and played with unmatched passion, whose brilliance on the pitch was matched only by his turbulence off it. His story is one of extraordinary triumph against overwhelming odds, followed by a long, painful fall that culminated in his untimely death in 2020. Yet even in tragedy, Maradona’s legend continues to inspire devotion and debate, a testament to his complicated but undeniable greatness.

The Rise of a Prodigy

From Villa Fiorito to Football Stardom

Diego Armando Maradona was born on October 30, 1960, in Lanús, Buenos Aires, but raised in Villa Fiorito, one of Argentina’s most impoverished shantytowns. His childhood home lacked clean water and paved roads, with his bricklayer father Don Diego working from 4 a.m. each day to support their family of eight. Despite these humble beginnings—or perhaps because of them—young Diego developed an extraordinary relationship with the football, treating it as both companion and escape.

At age eight, Maradona joined Las Cebollitas (“The Little Onions”), a youth team affiliated with Argentinos Juniors. The team’s coach, Francisco Cornejo, was immediately struck by the boy’s supernatural abilities. “When Diego came to Argentinos Juniors for trials, I was really struck by his talent and couldn’t believe he was only eight years old,” Cornejo later recalled. “We asked him for his ID card to check it, but he told us he didn’t have it on him. We were sure he was having us on because, although he had the physique of a child, he played like an adult.”

Las Cebollitas would go on to win 136 consecutive games with Maradona as their star, a testament to his transformative impact even at such a young age. By 14, he had signed with Argentinos Juniors’ senior team, making his first-division debut in 1976, just ten days before his 16th birthday. In his first professional match against Talleres de Córdoba, he nutmegged an opponent within minutes, announcing his arrival to Argentine football with audacious skill.

Breakthrough at Boca Juniors

After five remarkable years at Argentinos Juniors, where he scored 115 goals in 167 appearances, Maradona fulfilled a childhood dream by joining Boca Juniors in 1981. The transfer was itself a testament to his growing influence—when financial complications threatened to derail the move, fans literally took to the streets to raise funds, demonstrating the devotion he already commanded.

At Boca, Maradona immediately delivered on his promise, leading the team to the 1981 Metropolitano championship. His performances in the blue and gold jersey cemented his status as Argentina’s brightest star. In a memorable Superclásico against River Plate, he scored a goal after dribbling past several defenders, including goalkeeper Ubaldo Fillol, igniting the passionate La Bombonera stadium. This period, though brief, established an emotional connection between Maradona and Boca that would endure throughout his life.

By this time, Maradona had also become the youngest player ever to represent Argentina’s national team, making his debut at just 16 years and 120 days in February 1977. Though controversially left out of the 1978 World Cup squad that won on home soil (coach César Luis Menotti deemed him too young), he led Argentina’s under-20 team to victory in the 1979 FIFA World Youth Championship in Japan, showcasing his ability to dominate on the international stage.

“That day I felt I had held the sky in my hands.”

1986 World Cup: Divinity and Controversy

After stints at Barcelona (1982-1984) where injuries and controversy limited his impact, Maradona found his spiritual home at Napoli in Italy. But it was the 1986 World Cup in Mexico that would forever define his legacy and elevate him to mythical status. Leading an otherwise ordinary Argentine team, Maradona produced what many consider the greatest individual performance in World Cup history.

The quarter-final against England on June 22, 1986, encapsulated Maradona’s complex genius in 90 minutes. In the 51st minute, he scored the infamous “Hand of God” goal, punching the ball past goalkeeper Peter Shilton—an act of cunning deception that went undetected by officials. Just four minutes later, he scored what FIFA would later vote as the “Goal of the Century”—receiving the ball at midfield, Maradona slalomed past five English defenders before rounding Shilton and slotting home. The contrast between these two goals—one representing audacious cheating, the other sublime skill—perfectly captured Maradona’s duality.

The significance of these goals extended beyond sport. Coming just four years after the Falklands War between Argentina and Britain, Maradona later admitted the match carried political weight: “Although we had said before the game that football had nothing to do with the Malvinas [Falklands] War, we knew they had killed a lot of Argentine boys there, killed them like little birds. And this was revenge.” For many Argentines, Maradona’s triumph over England represented a symbolic national redemption.

Maradona continued his heroics in the semi-final against Belgium, scoring both goals in a 2-0 victory. In the final against West Germany, he provided the crucial assist for Jorge Burruchaga’s winning goal, securing Argentina’s second World Cup title. Throughout the tournament, Maradona scored or assisted 10 of Argentina’s 14 goals, a dominance rarely seen before or since in football’s greatest competition.

The 1986 World Cup transformed Maradona from a football star into a cultural icon. For Argentines, he became more than a player—he was a national hero who had conquered the world through sheer will and talent. The tournament cemented his place among football’s immortals and created the foundation of the Maradona mythology that endures today.

Peak and Controversies

Napoli’s Golden Era (1984-1991)

When Maradona arrived in Naples on July 5, 1984, he was greeted by 75,000 delirious fans at the Stadio San Paolo. Napoli had paid a world-record fee of $10.48 million to secure his services, and the city’s expectations were immense. Naples was a dysfunctional, impoverished southern Italian city that suffered from unemployment, organized crime, and discrimination from the wealthy industrial north. Maradona immediately identified with their struggle: “I want to become the idol of the poor children of Naples because they are like I was when I lived in Buenos Aires.”

What followed was nothing short of miraculous. Before Maradona’s arrival, Napoli had never won the Serie A title and had narrowly avoided relegation in the previous two seasons. At that time, Serie A was unquestionably the strongest league in the world, featuring superstars like Michel Platini, Zico, Karl-Heinz Rummenigge, and Marco van Basten at wealthy northern clubs like Juventus, AC Milan, and Inter.

Against these odds, Maradona led Napoli to their first-ever Serie A championship in 1986-87, followed by another title in 1989-90. He also guided them to victory in the 1987 Coppa Italia, the 1989 UEFA Cup, and the 1990 Italian Supercup. These achievements represented not just sporting success but a social revolution—a poor southern club triumphing over the aristocratic northern powers.

“For me, this title means a lot more than winning the World Cup. I won a youth World Cup in Tokyo and I won the World Cup in Mexico last year but on both occasions I was alone, I had no friends with me. Here, all my family, the city of Naples are with me because I consider myself a son of Naples.”

The celebrations after Napoli’s first Scudetto in 1987 were unprecedented. The entire city erupted in a month-long party. Cars honked their horns, fans danced on the roofs of stranded buses, and locals held mock funerals carrying coffins with Juventus markings. Outside the city’s largest cemetery, a banner read: “You don’t know what you have missed!” After decades of being looked down upon by northern Italians, who often greeted Napoli with banners reading “Welcome to Italy” and other territorial insults, the victory represented sweet revenge.

On the pitch, Maradona produced moments of genius that still circulate on highlight reels today: a 40-yard volleyed lob against Verona, a hat-trick against Lazio featuring an exquisite chip, an Olympic goal scored directly from a corner, and a one-step free-kick against Juventus that ended a 12-year winless streak against their northern rivals. His pre-match warm-up routine before the 1989 UEFA Cup semi-final against Bayern Munich, juggling to Opus’ “Live is Life,” remains one of football’s most enchanting pieces of footage.

The Dark Side: Addiction and Scandals

Behind the glory, however, lurked growing problems. Maradona’s cocaine addiction, which had begun during his time at Barcelona in 1982, intensified in Naples. “One touch and I felt like superman,” he later admitted. “In Naples, drugs were everywhere. And I took more and more there.” His addiction was so severe that he reportedly even used cocaine in the Vatican’s bathroom during a private audience with Pope John Paul II in 1985.

Maradona’s lifestyle in Naples was chaotic. He regularly missed or arrived late to training sessions and sometimes even matches. His former driver claimed that Diego slept with over 8,000 women during his time in Italy, despite living with his long-term girlfriend Claudia Villafañe. In September 1986, a paternity scandal erupted when Cristina Sinagra revealed that Maradona had fathered her son during a four-month affair. Maradona denied paternity for years, calling the child “just a mistake,” though a court ruling in 1993 confirmed he was the biological father.

Perhaps most troubling were Maradona’s connections to the Camorra, Naples’ notorious crime syndicate. His friendship with the Giuliano family, one of the most powerful Camorrista clans, led to a police investigation that uncovered 71 photos of Maradona with family members. These included images of him in a jacuzzi at their private residence and attending family weddings. When questioned, Maradona initially denied knowing about their criminal connections but later admitted: “They were like something out of The Untouchables movie about Al Capone. ‘Any problem you have is my problem’, they would say.”

Financial mismanagement also plagued Maradona throughout his career. Despite earning millions, he frequently faced tax problems. The Italian government claimed he owed €37 million in unpaid taxes from his time at Napoli, a dispute that continued until after his death when he was posthumously cleared by Italy’s Supreme Court of Cassation in January 2024.

The Fall: FIFA Ban and Career Decline

The beginning of the end came after the 1990 World Cup in Italy. When Argentina eliminated the host nation in the semi-finals in Naples, with Maradona scoring in the penalty shootout, he became a national villain. He had encouraged Neapolitans to support Argentina rather than Italy, playing on the north-south divide: “Naples has always been marginalized by the rest of Italy. It is a city that suffers the most unfair racism.”

This tactical move turned Italian public opinion against him. Gazzetta dello Sport labeled him the devil, while La Repubblica ran a survey asking readers to choose the historical figure they despised most—Maradona topped the poll ahead of war criminals and dictators. Overnight, he lost all political protection from the press, judiciary, and even Napoli football club.

In March 1991, disaster struck when Maradona tested positive for cocaine after a Serie A game against Bari. He received an unprecedented 15-month ban from football, effectively ending his Napoli career. Realizing he no longer enjoyed immunity, Diego fled back to Argentina in the middle of the night—a sad and undignified exit for someone who had given so much to the city.

Maradona himself claimed conspiracy: “When we started beating the northern teams, the establishment wanted to kill me. In 1990 more than ever. And in 1991, Antonio Mattarese [then president of Italian Football Federation] and Ferlaino made me pay.” His personal fitness trainer, Fernando Signorini, offered a more nuanced view: “No one was surprised to see Maradona test positive for cocaine. But the powers that be saw a great opportunity to finish him off.”

After serving his ban, Maradona returned to football with Sevilla in Spain for the 1992-93 season, but he was a shadow of his former self. Brief stints at Newell’s Old Boys in Argentina and a return to Boca Juniors followed, but his effectiveness had dramatically diminished. His final professional match came on October 25, 1997, a fitting full circle as he played his last game for his beloved Boca.

The 1994 World Cup in the United States offered a brief glimpse of Maradona’s enduring talent but ended in another scandal. After scoring against Greece and producing one of the most memorable goal celebrations—running toward a sideline camera with a distorted face of pure emotion—he tested positive for ephedrine and was sent home in disgrace. His wild-eyed celebration would later be viewed as evidence of his substance abuse issues. This marked his final appearance for Argentina, bringing his international career to a tragic conclusion.

Personal Struggles and Tragedy

Health Crisis and Public Decline

The years following Maradona’s retirement were marked by a series of health crises that played out painfully in the public eye. His weight ballooned to dangerous levels, reaching approximately 280 pounds (130 kg) at his heaviest. The combination of cocaine addiction, alcohol abuse, and an undisciplined lifestyle had taken a devastating toll on his body.

In January 2000, Maradona suffered a severe heart attack while vacationing in Punta del Este, Uruguay. Doctors attributed the cardiac event to cocaine use, confirming what many had long suspected about his ongoing substance abuse issues. This health scare marked the beginning of a two-decade battle with serious medical problems.

In 2004, Maradona was hospitalized with heart and respiratory problems. Images of him being carried into the Suárez Clinic in Buenos Aires shocked the world. With his bloated face and labored breathing, he barely resembled the athletic phenomenon who had once dazzled on football pitches around the globe. Doctors described his condition as “critical” for several days before he stabilized.

“I was, I am, and I always will be a drug addict. A person who gets involved with drugs has to fight it every day.”

In March 2005, Maradona underwent gastric bypass surgery in Colombia to address his obesity. The procedure helped him lose significant weight, but his health problems continued. In 2007, he was hospitalized again for hepatitis and alcohol-related issues. After being discharged and readmitted multiple times, he was eventually transferred to a psychiatric clinic specializing in alcohol problems.

Perhaps most disturbing were Maradona’s public meltdowns, which often occurred during Argentina’s matches at major tournaments. During the 2018 World Cup in Russia, television cameras captured him behaving erratically during Argentina’s match against Nigeria, with white residue visible on the glass in front of his seat. Though he blamed his behavior on consuming “lots of wine,” many viewers recognized the signs of substance abuse.

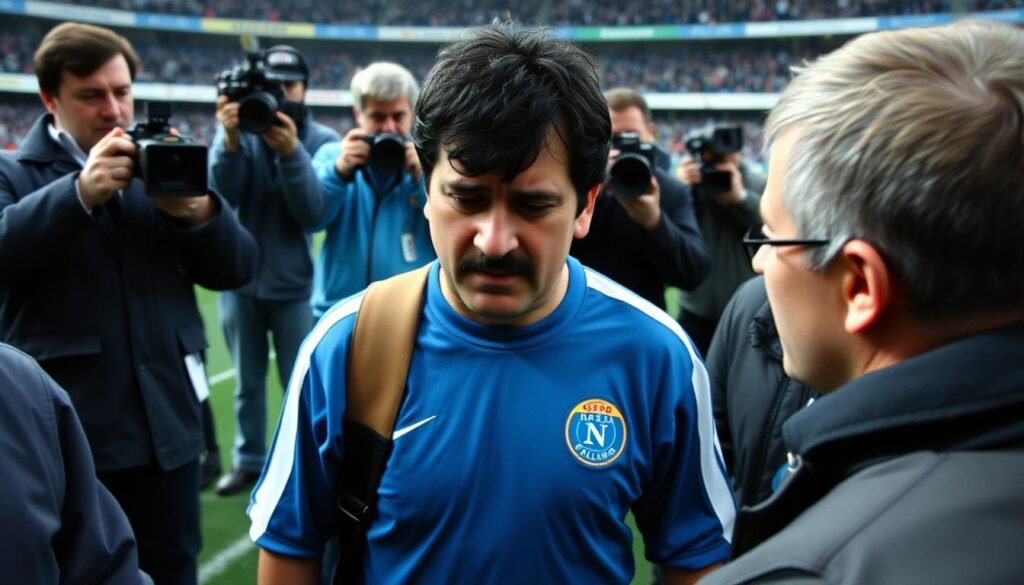

Failed Coaching Career

Despite his personal troubles, Maradona harbored ambitions of replicating his playing success as a coach. His managerial career began inauspiciously with brief, unsuccessful stints at Argentine clubs Deportivo Mandiyú and Racing Club in the mid-1990s. After a long hiatus, he returned to coaching in 2008 when he was surprisingly appointed head coach of the Argentina national team.

His tenure with Argentina produced mixed results. The team struggled through 2010 World Cup qualification, only securing their place in the final two matches. At the tournament in South Africa, Argentina started promisingly with group stage victories but were ultimately humiliated in a 4-0 quarter-final defeat to Germany. Maradona’s tactical naivety was exposed at the highest level, and the Argentine Football Association opted not to renew his contract.

What followed was a nomadic coaching career that took him to the United Arab Emirates (Al Wasl), Belarus (Dynamo Brest), Mexico (Dorados de Sinaloa), and back to Argentina (Gimnasia de La Plata). None of these appointments yielded significant success, and many seemed motivated more by financial considerations than genuine football ambitions. His erratic behavior on the sidelines often overshadowed his teams’ performances.

Perhaps the most telling example of Maradona’s coaching limitations came during his time with Dorados in Mexico’s second division. The Netflix documentary series “Maradona in Mexico” captured his tenure, showing a man who could still inspire devotion but struggled with the tactical and organizational demands of modern coaching. Despite some initial success, he failed to achieve promotion and resigned citing health reasons.

His final coaching position was with Gimnasia de La Plata in Argentina’s top flight. He took over in September 2019 with the team struggling near the bottom of the table. Though he brought attention and enthusiasm to the modest club, results remained inconsistent. He was still Gimnasia’s coach when he died in November 2020, with the team having won just 8 of 21 matches under his guidance.

Final Days and Death

On November 2, 2020, Maradona was admitted to a hospital in La Plata, Argentina, with signs of depression. Initial reports suggested his condition was not serious, but a day later, he underwent emergency brain surgery to treat a subdural hematoma—a blood clot on the brain. The operation was successful, and he was released on November 12 to continue recovery as an outpatient at a private residence in Tigre, Buenos Aires Province.

Just thirteen days after his surgery, on November 25, 2020, Maradona suffered cardiac arrest at his home and died. He was 60 years old. The news of his death triggered an outpouring of grief across Argentina and the football world. The Argentine government declared three days of national mourning, while thousands of fans gathered outside the Casa Rosada presidential palace where his body lay in state.

The circumstances surrounding Maradona’s death quickly became controversial. In May 2021, a medical board investigating his treatment concluded that his medical team had acted in an “inappropriate, deficient, and reckless manner.” Seven health professionals, including his personal doctor Leopoldo Luque and psychiatrist Agustina Cosachov, were charged with homicide over their alleged negligence in his care.

The investigation revealed disturbing details about Maradona’s final days. Despite his serious condition, he reportedly received inadequate monitoring and care. Prosecutors alleged that his medical team knew he was at high risk of death but did nothing to prevent it. The criminal case against the medical professionals is ongoing, with a trial scheduled to begin in March 2025.

“We were shocked when we saw the poor and inadequate home hospitalization that Diego Maradona had before he died—a situation that unfortunately led to his death.”

Maradona’s funeral itself became chaotic. His coffin was draped in the Argentine flag and three Maradona number 10 shirts (Argentinos Juniors, Boca Juniors, and Argentina). As tens of thousands of fans filed past to pay their respects, the situation grew increasingly tense. When mourners broke into the presidential palace’s inner courtyard and clashed with police, authorities were forced to cut the public viewing short.

On November 26, 2020, Diego Armando Maradona was buried next to his parents at the Jardín de Bella Vista cemetery in Buenos Aires. The private ceremony marked the final chapter in the tumultuous life of football’s most controversial genius. Yet even in death, the disputes surrounding Maradona continued, with family members engaging in legal battles over his estate, estimated to be worth between $75 million and $100 million.

Legacy of a Flawed Icon

Cultural Impact in Argentina and Naples

Few athletes have ever been so deeply woven into the cultural fabric of multiple societies as Diego Maradona. In Argentina, he transcended sport to become a national symbol—a working-class hero who conquered the world through sheer talent and will. His impact was so profound that sociologist Eduardo Archetti described him as “the only Argentine who truly belongs to the people.” When Argentina won the 2022 World Cup, their first since Maradona’s 1986 triumph, players and fans alike invoked his spirit, suggesting he was watching over them from above.

In Naples, Maradona’s legacy is perhaps even more extraordinary. He arrived in a downtrodden city suffering from poverty, unemployment, and northern Italian prejudice, and transformed not just its football team but its collective self-esteem. During his time there, murals depicting him appeared throughout the city, some comparing him to San Gennaro, Naples’ patron saint. In Neapolitan households, photos of Maradona were displayed next to religious icons, and thousands of babies were named after him.

This devotion continues decades after his departure. When his daughter Dalma visited Naples in 2011, people knelt before her in the streets. Following his death, the city renamed its stadium Stadio Diego Armando Maradona, while shrines and tributes appeared throughout Naples’ narrow streets. As journalist John Ludden noted in his book “Once Upon a Time in Naples,” “San Gennaro has retained his mythical status since 305AD. Seventeen-hundred years from now, Maradona will still be worshipped as a God too. The God of Naples.”

Beyond these two locations, Maradona’s cultural impact spread globally. In Bangladesh, a country with no historical connection to Argentina, thousands of fans still support the Albiceleste because of Maradona’s 1986 World Cup heroics. In Cuba, where he spent time in rehabilitation, he developed a close friendship with Fidel Castro and became a symbol of anti-imperialism. His face appears on murals, t-shirts, and tattoos worldwide, transcending football to become a universal icon of rebellious genius.

Perhaps the most unusual testament to Maradona’s cultural impact is the Church of Maradona (Iglesia Maradoniana), a religion founded in Rosario, Argentina, in 1998. With over 120,000 “baptized” members worldwide, the church celebrates Diego’s birthday as Christmas and the year of his debut (1976) as year one in their calendar. While partly tongue-in-cheek, the church reflects the quasi-religious devotion Maradona inspired.

The Eternal Debate: Genius vs. Self-Destruction

Maradona’s legacy is forever entangled in the debate between his unparalleled football genius and his self-destructive tendencies. Those who played with or against him are nearly unanimous in their assessment of his sporting greatness. “The things I could do with a football, he could do with an orange,” said Michel Platini. “There will never be anyone like Maradona again, not even if Messi wins three World Cups,” declared Hector Enrique, his 1986 World Cup teammate.

The Case for Greatness

- Led Argentina to World Cup glory in 1986 with perhaps the greatest individual tournament performance ever

- Transformed Napoli from relegation candidates to two-time Italian champions

- Overcame poverty, class prejudice, and targeted violence on the pitch

- Possessed technical skills that many consider unmatched in football history

- Inspired devotion across generations and cultures

- Stood up for the oppressed and challenged football’s establishment

The Case Against

- Cocaine addiction that spanned decades and ultimately contributed to his death

- Cheated on the pitch (Hand of God) and failed drug tests

- Associations with organized crime figures

- Denied paternity of his son for years

- Squandered much of his talent through poor lifestyle choices

- Erratic behavior and public meltdowns that tarnished his image

This duality makes Maradona a complex figure to assess. Was he a flawed genius or a wasted talent? The answer likely lies somewhere in between. His background provides important context—raised in extreme poverty, thrust into fame as a teenager, and surrounded by enablers who profited from his talent while ignoring his demons. As journalist Marcela Mora y Araujo noted, “Maradona was never equipped to deal with the pressures of being Maradona.”

Some argue that Maradona’s flaws were inseparable from his genius—that the same rebellious spirit that allowed him to challenge authority on the pitch also led him to self-destructive behavior off it. Others suggest that his tragic arc makes his achievements more remarkable. To reach such heights while battling addiction and personal turmoil speaks to his extraordinary natural gifts.

The debate extends to his place in football history. The eternal question of whether Maradona, Pelé, or now Lionel Messi deserves recognition as the greatest player ever remains unresolved. In 2000, FIFA attempted to settle the matter by naming Maradona and Pelé joint winners of their Player of the Century award—Maradona won the internet poll with 53.6% of votes, while a “Football Family” committee gave their award to Pelé.

What’s undeniable is that Maradona’s impact transcended statistics. His 259 goals in 491 club games and 34 goals in 91 international appearances, while impressive, don’t fully capture his influence. He inspired not just through goals and assists but through moments of magic that seemed to defy physics and logic. As FourFourTwo magazine wrote when ranking him the greatest player of all time in 2017: “If you’ve seen Diego Maradona with a football at his feet, you’ll understand.”

Cultural Tributes and Enduring Fascination

Maradona’s complex legacy continues to inspire artistic and cultural works that attempt to capture his contradictions. Asif Kapadia’s 2019 documentary “Diego Maradona” used over 500 hours of never-before-seen footage to create a nuanced portrait of the man behind the myth. The film explores how “Diego” (the vulnerable boy from the slums) and “Maradona” (the larger-than-life public persona) became increasingly disconnected as fame and addiction took their toll.

Other notable works include the Amazon Prime series “Maradona: Blessed Dream” (2021), which dramatized his life story across ten episodes, and countless books examining different aspects of his career and personality. Argentine rock musicians like Andrés Calamaro (“Maradona”) and Fito Páez (“Y dale alegría a mi corazón”) wrote songs celebrating his impact, while the Spanish band Mano Negra’s “Santa Maradona” became an anthem for his devotees.

In the art world, Maradona has been immortalized in countless murals, paintings, and sculptures. The most famous is perhaps the 20-foot mural in the San Paolo district of Naples, which has become a pilgrimage site for football fans. After his death, new tributes appeared globally—from Buenos Aires to Bangladesh, Naples to New Delhi—reflecting his universal appeal.

Digital culture has also embraced Maradona’s legacy. His “Hand of God” and “Goal of the Century” against England are among the most viewed football clips online, while his pre-match warm-up to “Live is Life” has been watched millions of times on YouTube. Memes and social media tributes continue to introduce his genius to younger generations who never saw him play live.

Perhaps most significantly, Maradona’s influence lives on through the players he inspired. Lionel Messi, often considered Maradona’s heir, wore a Newell’s Old Boys shirt with Maradona’s number 10 after scoring for Barcelona following Diego’s death. After Argentina’s 2022 World Cup victory, Messi was photographed with the trophy while looking up at the sky—a moment widely interpreted as acknowledging Maradona’s spiritual presence.

Even in death, Maradona continues to provoke debate, inspire devotion, and embody contradictions. His legacy is not just about football but about class, politics, addiction, media, and the price of fame. As journalist Marcela Mora y Araujo wrote: “Maradona was never just a footballer. He was a complicated, self-contradictory symbol of Argentine potential and failure, of the country’s perpetual sense of victimhood and superiority, its technical brilliance and its inability to quite fulfill its promise.”

Diego Armando Maradona’s life story reads like a modern Greek tragedy—a tale of extraordinary talent, dizzying heights, devastating falls, and ultimately, premature death. From the dirt streets of Villa Fiorito to the pinnacle of world football and back down through a spiral of addiction and health problems, his journey captivated millions and left an indelible mark on global culture.

What makes Maradona’s legacy so enduring is precisely this complexity. He was neither saint nor sinner but a profoundly human figure whose flaws were as outsized as his talents. He represented the best and worst of Argentina—its creativity, passion, and rebellious spirit alongside its volatility, excess, and self-sabotage. He gave hope to the marginalized by proving that a boy from the slums could conquer the world, yet his self-destructive tendencies served as a cautionary tale about the perils of fame.

On the pitch, Maradona’s achievements stand among the greatest in football history. He won trophies that seemed impossible—leading a modest Napoli side to two Serie A titles against wealthy northern powerhouses and carrying Argentina to World Cup glory in 1986. He produced moments of such sublime skill that they transcended sport to become cultural touchstones. The “Goal of the Century” against England remains the perfect encapsulation of his genius—a display of vision, balance, speed, control, and courage that still takes the breath away decades later.

“When Diego scored that second goal against us, I felt like applauding. It was impossible to score such a beautiful goal. He’s the greatest player of all time, by a long way.”

Off the pitch, his life was marked by chaos and contradiction. The cocaine addiction that began in Barcelona intensified in Naples and haunted him until his death. His relationships were complicated—he married his childhood sweetheart Claudia Villafañe yet fathered children with other women and denied paternity for years. He befriended both Fidel Castro and the Camorra crime syndicate. He spoke out against imperialism yet evaded taxes and lived lavishly.

These contradictions make Maradona impossible to reduce to simple judgments. He was neither hero nor villain but something more nuanced—a flawed genius whose humanity was always visible beneath the mythology that surrounded him. As Eduardo Galeano wrote in “Soccer in Sun and Shadow”: “No one has ever controlled the ball like him… But the pleasure of seeing him play came always with the fear of seeing him die.”

That fear was realized on November 25, 2020, when Maradona’s heart finally gave out after years of abuse. Yet even in death, his influence endures. In Naples, his murals are still adorned with fresh flowers. In Argentina, his number 10 shirt remains sacred. Around the world, clips of his greatest moments continue to astonish new generations of fans who never saw him play live.

Perhaps the most fitting epitaph for Maradona comes from his own words. When asked about his legacy, he once said: “I made mistakes, and I paid for them. But the ball is still clean.” For all his flaws and failings, when Diego Maradona had a football at his feet, he created art that will live forever in the collective memory of the beautiful game.

Explore More Football Legends

Discover the stories behind other iconic figures who shaped the beautiful game through triumph and adversity.