Alexander the Great: Conqueror of the World

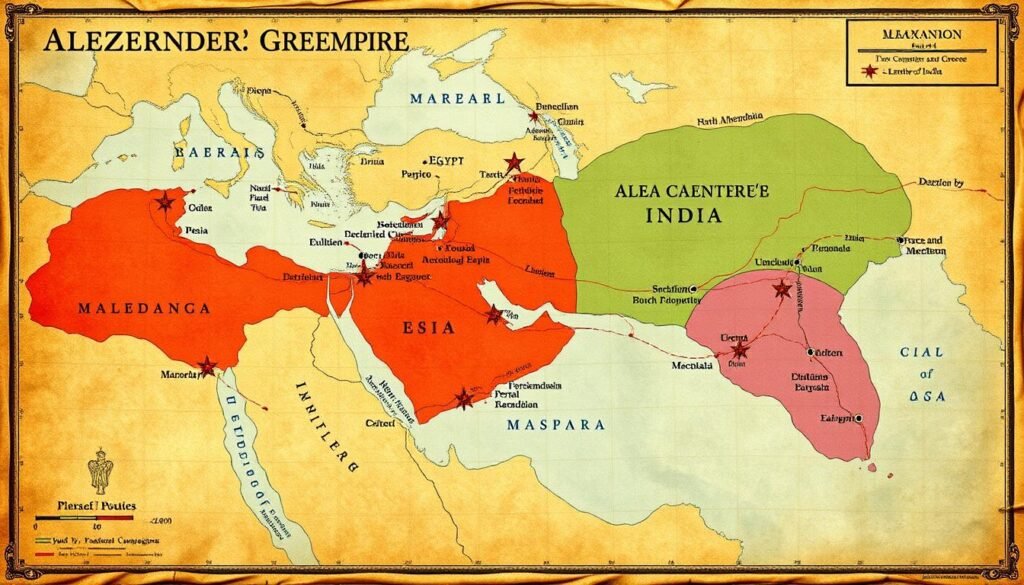

Alexander the Great (356-323 BCE) stands as one of history’s most brilliant military commanders and empire builders. In just 13 years, this Macedonian king conquered the mighty Persian Empire and created one of the ancient world’s largest domains, stretching from Greece to northwestern India. His military genius, charismatic leadership, and cultural vision transformed the ancient world and ushered in the Hellenistic era. This article explores Alexander’s remarkable campaigns, innovative battle strategies, and enduring legacy that continues to influence military and political thought to this day.

Early Life and Education

Young Alexander receiving education from the philosopher Aristotle

Born in 356 BCE in Pella, Macedonia, Alexander was the son of King Philip II and Queen Olympias. From an early age, he displayed remarkable intelligence and physical prowess. At age 13, his father appointed the renowned philosopher Aristotle as his tutor, who instilled in him a love for literature, science, medicine, and philosophy. This education would later influence Alexander’s approach to governance and cultural exchange.

Alexander’s military training began early under Leonidas of Epirus, who taught him to fight, ride, and endure hardships. By age 16, Philip left him in charge of Macedonia while away on campaign, demonstrating his early capability for leadership. His first significant military achievement came at the Battle of Chaeronea in 338 BCE, where the 18-year-old Alexander led the decisive cavalry charge that defeated the Sacred Band of Thebes, previously considered invincible.

One famous anecdote from his youth involves the taming of Bucephalus, a horse deemed untamable. Recognizing the horse was afraid of its own shadow, the 12-year-old Alexander turned the animal toward the sun and successfully mounted it. Impressed, Philip reportedly said: “My son, seek out a kingdom worthy of yourself, for Macedonia is too small for you.” Bucephalus would remain Alexander’s faithful companion throughout most of his campaigns.

Rise to Power

In 336 BCE, Philip II was assassinated by his bodyguard Pausanias during his daughter’s wedding celebrations. At just 20 years old, Alexander claimed the Macedonian throne. His succession was not without challenges—he swiftly eliminated potential rivals and quashed rebellions in northern Greece to secure his position.

As the historian Arrian notes: “Alexander’s first act as king was to punish his father’s murderers and conduct his funeral with magnificent pomp and ceremony.” With his position in Macedonia and Greece secured, Alexander turned his attention to his father’s unfulfilled ambition: the invasion of the Persian Empire.

Alexander’s ascension to the Macedonian throne at age 20

Before departing for Asia, Alexander needed to ensure Greece would not revolt during his absence. He convened the League of Corinth, where he was appointed commander of the Greek forces against Persia. He then appointed his trusted general Antipater as regent of Macedonia and Greece, and in 334 BCE, crossed the Hellespont (modern Dardanelles) with approximately 37,000 men to begin his Persian campaign.

Military Genius and Strategy

Alexander’s military brilliance stemmed from his innovative tactics, personal courage, and ability to adapt to different battlefield conditions. His army consisted of several key components:

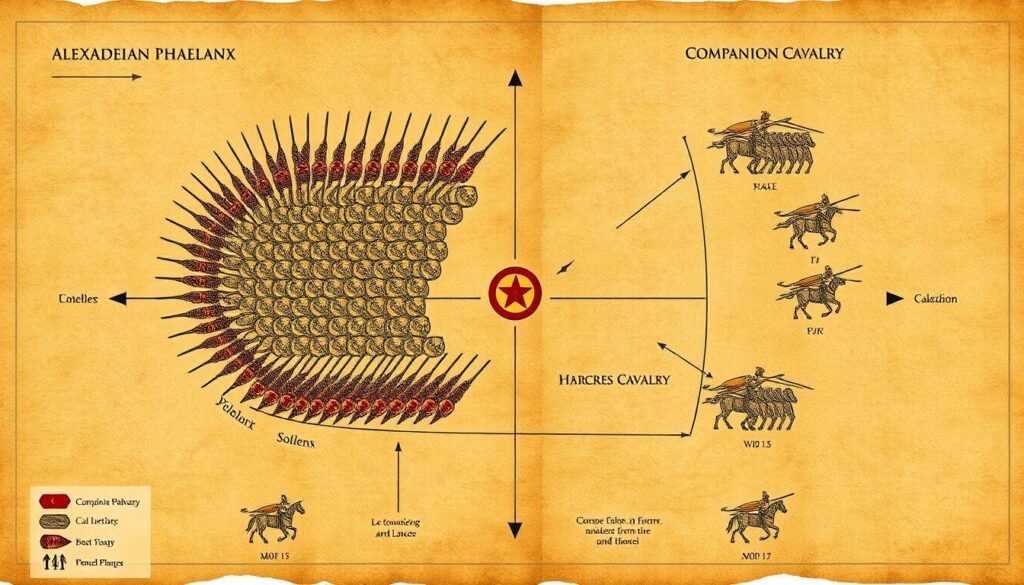

The Macedonian Phalanx

The backbone of Alexander’s infantry was the phalanx—a formation of soldiers armed with sarissas (18-foot spears). These tightly-packed formations created an impenetrable wall of spear points that could devastate enemy infantry.

Companion Cavalry

Alexander’s elite heavy cavalry, known as the Companion Cavalry, was his primary striking force. Led personally by Alexander, this unit would deliver the decisive blow in many battles, charging at critical moments to break enemy lines.

Combined Arms Approach

Alexander pioneered the effective coordination of different military units. He used light infantry, archers, and skirmishers to support his phalanx, while cavalry protected the flanks and exploited breakthroughs.

Siege Warfare

Alexander revolutionized siege warfare with innovative approaches to conquering fortified positions, as demonstrated at Tyre where he built a causeway to reach the island city.

Tactical diagram of Alexander’s typical battle formation

Alexander’s leadership style was another key to his success. Unlike many commanders of his time, he led from the front, often placing himself in considerable danger. This inspired tremendous loyalty among his troops, who would follow him into seemingly impossible situations. As Plutarch observed: “His men were willing to follow him anywhere, even through hardships that would have broken other armies.”

Major Battles and Conquests

Battle of Granicus (334 BCE)

Alexander’s first major encounter with Persian forces occurred at the Granicus River in modern-day Turkey. Despite being outnumbered, Alexander led a daring cavalry charge across the river, personally engaging in the thick of combat. During this battle, he narrowly escaped death when Cleitus the Black saved him from a Persian nobleman’s axe. The victory secured western Asia Minor for Alexander and demonstrated his bold tactical approach.

Alexander leading the cavalry charge at the Battle of Granicus

Battle of Issus (333 BCE)

At Issus, Alexander faced King Darius III himself, commanding a significantly larger Persian army. Alexander’s tactical genius shone as he exploited a narrow coastal plain that neutralized the Persian numerical advantage. The decisive moment came when Alexander led his Companion Cavalry in a charge directly at Darius, causing the Persian king to flee and abandoning his army to defeat. This victory gave Alexander control of the eastern Mediterranean coastline.

Siege of Tyre (332 BCE)

The island city of Tyre, separated from the mainland by half a mile of water, presented Alexander with one of his greatest challenges. When the city refused to surrender, Alexander ordered the construction of a causeway to reach the island—an engineering marvel of the ancient world. After a seven-month siege utilizing innovative naval tactics and siege engines, Tyre fell. Alexander’s determination and ingenuity during this siege demonstrated his unwavering resolve and adaptability.

The construction of the causeway during the Siege of Tyre

Battle of Gaugamela (331 BCE)

The decisive battle against the Persian Empire took place at Gaugamela in modern-day Iraq. Despite being outnumbered at least 2:1, Alexander’s tactical genius prevailed. He placed his forces at an angle to the Persian line, forcing Darius to extend his line to prevent being outflanked. When the Persian cavalry moved to counter this threat, it created a gap in their center. Alexander led his Companion Cavalry in a charge directly at Darius, who once again fled. This victory effectively ended the Persian Empire and made Alexander the ruler of Asia.

“Alexander’s victory at Gaugamela was not merely a triumph of arms but a masterpiece of tactical genius. He defeated an army many times the size of his own through superior discipline, leadership, and an uncanny ability to identify and exploit the critical moment in battle.”

Conquest of India and the Eastern Campaigns

By 327 BCE, with the Persian Empire firmly under his control, Alexander turned his attention eastward toward India. His army crossed the Hindu Kush mountains and entered the Indus Valley. Along the way, he captured the supposedly impregnable mountain fortress of Aornos (modern Pir-Sar), demonstrating his skill in mountain warfare.

Alexander’s army traversing the Hindu Kush mountains en route to India

In 326 BCE, Alexander faced King Porus at the Battle of the Hydaspes River. This battle presented a new challenge: war elephants. Despite the formidable obstacle, Alexander devised a brilliant strategy, crossing the river at night upstream from Porus’s position and outflanking the Indian forces. After a hard-fought battle, Alexander defeated Porus but, impressed by the Indian king’s courage, reinstated him as a vassal ruler over an even larger territory.

Alexander intended to press further into India, but at the Hyphasis River (modern Beas), his exhausted army mutinied, refusing to march farther. After three days of attempting to persuade them, Alexander reluctantly agreed to turn back. As Arrian records: “Alexander was more affected by grief than anger at his men’s refusal, for he saw in it the end of his hopes and dreams of conquest.”

The return journey proved as challenging as the conquest. Part of the army traveled by sea under Admiral Nearchus, while Alexander led the remainder through the harsh Gedrosian Desert (modern Baluchistan), resulting in significant casualties from heat and thirst. This grueling march is often considered one of the most difficult military expeditions in ancient history.

Empire Administration and Cultural Policy

Alexander’s approach to governing his vast empire was revolutionary for its time. Rather than simply imposing Greek rule and culture, he adopted a policy of cultural fusion that would have lasting implications:

Alexander adopting Persian royal attire, symbolizing his policy of cultural fusion

Respecting Local Customs

In conquered territories, Alexander often retained local administrative systems and respected indigenous religious practices. In Egypt, he was proclaimed Pharaoh and made sacrifices to Egyptian gods. In Babylon, he ordered the restoration of temples and religious sites. This pragmatic approach helped stabilize his rule over diverse populations.

The Policy of Fusion

Alexander actively promoted the integration of Persian and Macedonian cultures. He arranged the mass wedding at Susa in 324 BCE, where he and 80 of his officers married Persian noblewomen. He also incorporated Persians into his army and administration, even forming a unit of Persian youth trained in Macedonian military techniques.

This policy of cultural fusion was not always popular among his Macedonian veterans, who resented the elevation of “barbarians” to positions of authority. The tension culminated in a mutiny at Opis in 324 BCE, which Alexander quelled through a combination of firmness and reconciliation.

“His aim was not to conquer the world but to unite it, not merely to defeat the Persians but to incorporate them into a new international order.”

City Founding

Alexander founded numerous cities throughout his empire, the most famous being Alexandria in Egypt. These cities served as administrative centers, trade hubs, and cultural melting pots where Greek and local traditions could intermingle. By some accounts, he established over 70 cities, many named Alexandria, which became centers of Hellenistic culture for centuries.

The Hellenistic Era: Alexander’s Cultural Legacy

Alexander’s conquests initiated what historians call the Hellenistic Period (323-31 BCE), characterized by the spread of Greek culture throughout the former Persian Empire and beyond. This cultural diffusion had profound and lasting effects:

The Library of Alexandria, one of the greatest achievements of the Hellenistic era

Language and Literature

Greek became the lingua franca of the eastern Mediterranean and much of the Near East, facilitating trade, administration, and cultural exchange. The Hellenistic period saw the development of Koine Greek, a common dialect that would later become the language of the New Testament.

Science and Philosophy

Greek scientific and philosophical traditions spread throughout Alexander’s former empire. Alexandria in Egypt became a center of learning, home to the famous Library and the Mouseion, where scholars like Euclid, Archimedes, and Eratosthenes made groundbreaking discoveries in mathematics, physics, and geography.

Art and Architecture

Hellenistic art combined Greek aesthetic principles with Eastern influences, creating distinctive styles characterized by greater realism, emotional intensity, and technical virtuosity. Monumental buildings combining Greek and local architectural elements appeared throughout the Hellenistic kingdoms.

The cultural synthesis Alexander initiated continued long after his death, as his empire was divided among his generals (the Diadochi). These successor kingdoms—the Ptolemaic Empire in Egypt, the Seleucid Empire in Asia, and the Antigonid Dynasty in Macedonia—maintained and developed Hellenistic culture until they were eventually absorbed by the Roman Empire.

Death and Succession Crisis

In June 323 BCE, Alexander fell ill after attending a banquet in Babylon. After suffering from fever for ten days, he died on June 10 or 11 at the age of 32. The exact cause of his death remains debated among historians, with theories ranging from malaria or typhoid fever to poisoning.

Alexander on his deathbed in Babylon, surrounded by his generals

According to Plutarch, when asked to whom he left his kingdom, Alexander replied, “To the strongest.” This ambiguous answer set the stage for the Wars of the Diadochi (Successors), as his generals fought for control of the empire. Initially, they attempted to maintain the empire’s unity by recognizing Alexander’s half-brother Philip III Arrhidaeus and his posthumous son Alexander IV as joint kings under a regency.

However, this arrangement quickly collapsed as ambitious generals carved out their own territories. By 301 BCE, after the Battle of Ipsus, the empire was effectively divided into four major kingdoms:

- The Ptolemaic Kingdom in Egypt under Ptolemy I Soter

- The Seleucid Empire in Asia under Seleucus I Nicator

- The Kingdom of Macedonia under Cassander

- The Kingdom of Pergamon under Lysimachus (later Attalid dynasty)

Despite the political fragmentation, these successor kingdoms maintained many of Alexander’s policies, particularly his approach to cultural fusion and city-building. The Hellenistic world he created would endure for nearly three centuries until the Roman conquest.

Military Innovations and Tactical Legacy

Alexander’s military achievements went beyond mere conquest; he revolutionized warfare in ways that influenced military thinking for centuries:

Alexander’s innovative siege engines revolutionized ancient warfare

Combined Arms Warfare

Alexander perfected the integration of different military units—heavy infantry, light infantry, archers, and cavalry—into a cohesive fighting force. This combined arms approach became a standard in military organization for centuries to come.

Logistics and Supply

To support his rapidly moving army across vast distances, Alexander developed sophisticated logistics systems. He employed engineers, surveyors, and scientists who traveled with the army to build bridges, roads, and siege equipment as needed.

Adaptability

Perhaps Alexander’s greatest military strength was his adaptability. He modified his tactics based on terrain and opponents, incorporating useful elements from other military traditions. After encountering war elephants in India, for example, he began to incorporate them into his own army.

Alexander’s campaigns were studied by later military leaders from Hannibal and Julius Caesar to Napoleon Bonaparte. His emphasis on mobility, decisive battle, and personal leadership became enduring principles of military strategy.

“Alexander’s campaigns remain a model of strategic planning and tactical execution. His ability to adapt to different enemies and terrains while maintaining strategic focus exemplifies the highest qualities of generalship.”

Timeline of Alexander’s Conquests

| Year (BCE) | Event | Significance |

| 336 | Ascension to throne after Philip II’s assassination | Secured power in Macedonia and Greece |

| 334 | Crossing of Hellespont; Battle of Granicus | First victory against Persian forces; secured Asia Minor |

| 333 | Battle of Issus | Defeated Darius III; gained control of eastern Mediterranean |

| 332 | Siege of Tyre; Conquest of Egypt | Eliminated Persian naval bases; founded Alexandria |

| 331 | Battle of Gaugamela | Decisive defeat of Persian Empire; Alexander proclaimed King of Asia |

| 330 | Capture of Persepolis; death of Darius III | Symbolic end of Persian Empire; Alexander adopted Persian court customs |

| 329-327 | Campaigns in Bactria and Sogdiana | Consolidated control of eastern Persian provinces |

| 326 | Invasion of India; Battle of Hydaspes | Defeated King Porus; reached easternmost extent of empire |

| 325-324 | Return through Gedrosian Desert; arrival at Susa | Completed circumnavigation of Arabian Peninsula; implemented fusion policies |

| 323 | Death in Babylon | Empire divided among generals (Diadochi) |

Key Achievements and Legacy

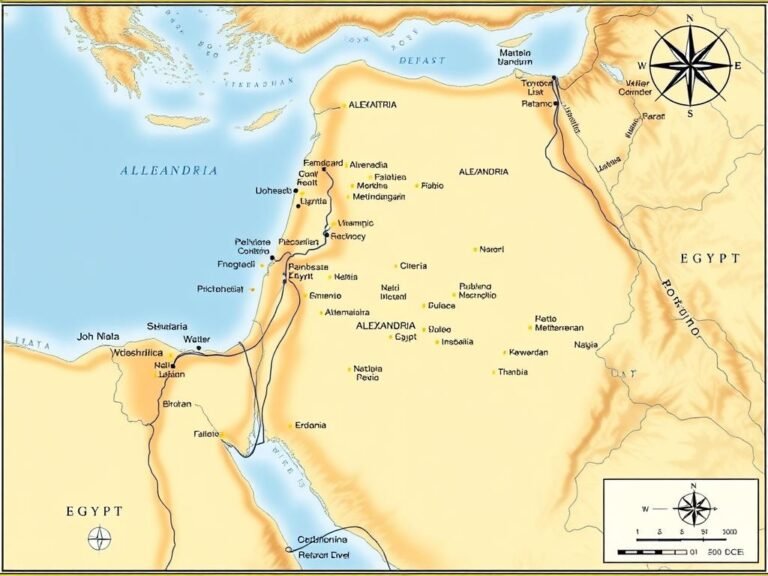

The extent of Alexander’s empire at its height, spanning from Greece to northwestern India

Military Achievements

- Created one of history’s largest empires in just 13 years

- Never lost a battle despite often facing numerically superior forces

- Revolutionized siege warfare with innovative techniques

- Developed effective combined arms tactics that influenced military thinking for centuries

- Led one of history’s longest sustained military campaigns, covering over 20,000 miles

Cultural Impact

- Spread Greek language, art, architecture, and philosophy throughout the Near East and Central Asia

- Established over 70 cities, many of which became important cultural and commercial centers

- Created conditions for unprecedented cultural exchange between East and West

- Initiated the Hellenistic Period, a time of great scientific and philosophical achievement

- Developed a model of cultural respect and integration that influenced later empires

Political Legacy

- Demonstrated the possibility of a multi-ethnic empire under unified rule

- Established administrative systems that successor states continued to use

- Created trade networks connecting Europe, Africa, and Asia

- Inspired later conquerors from Caesar to Napoleon

- Became a symbol of leadership excellence and ambition

Modern Influence and Relevance

Alexander the Great’s influence extends far beyond the ancient world. His life and achievements continue to resonate in modern leadership theory, geopolitics, and popular culture:

Modern military strategists studying Alexander’s battle tactics at a war college

Leadership Studies

Alexander exemplifies many qualities valued in modern leadership theory: strategic vision, adaptability, personal courage, and the ability to inspire followers. Business schools and military academies continue to study his methods of motivation and decision-making under pressure.

Geopolitical Relevance

The regions Alexander conquered—the Middle East, Central Asia, and the Eastern Mediterranean—remain geopolitically significant today. His campaigns through Afghanistan and Pakistan traverse territories that continue to be strategically important in modern conflicts.

Cultural Symbolism

Alexander has become a cultural icon representing ambition, youth, and the pursuit of greatness. He appears in countless works of literature, art, film, and even video games. Both Western and Eastern traditions claim him as part of their heritage, demonstrating his cross-cultural significance.

“Alexander’s vision of a world united by common culture and commerce, while never fully realized in his lifetime, anticipated the globalized world we inhabit today.”

Perhaps most significantly, Alexander represents the impact that a single visionary leader can have on world history. In just over a decade, he redrew the map of the known world and set in motion cultural exchanges that would shape civilization for centuries to come.

Conclusion

Modern statue of Alexander the Great in Thessaloniki, Greece

Alexander the Great’s life and achievements stand as one of history’s most remarkable stories. In just 32 years, he transformed the ancient world through military genius, cultural vision, and sheer force of will. His empire, though short-lived as a unified entity, created the foundation for the Hellenistic world that would flourish for centuries.

What makes Alexander truly “Great” is not merely the territory he conquered but the lasting impact of his vision. By spreading Greek culture while respecting and incorporating local traditions, he created a new cultural synthesis that transcended the narrow nationalism of his time. The libraries, academies, and cities he established became centers of learning and commerce that preserved and advanced human knowledge.

As the historian Arrian concluded: “Whatever criticism one might level at Alexander, his greatness cannot be denied. No other individual in ancient history accomplished so much in so short a time or left such an indelible mark on the world.” More than two millennia after his death, Alexander remains the standard against which ambitious leaders measure themselves—a testament to his enduring place in human history as the conqueror who forever changed the world.

Download Alexander’s Military Timeline

Track the rapid expansion of Alexander’s empire with our detailed year-by-year timeline of major battles and conquests. Perfect for students and history enthusiasts.

Download Alexander’s Conquest Map

Visualize Alexander’s incredible 11-year campaign across three continents with our detailed, printable map showing all major battles, routes, and conquered territories.

Explore the Hellenistic Legacy

Discover how Alexander’s conquests shaped art, science, and philosophy for centuries. Our illustrated guide covers the major cultural developments of the Hellenistic era.

Test Your Knowledge: Alexander the Great Quiz

How much do you know about history’s greatest conqueror? Challenge yourself with our comprehensive quiz covering Alexander’s life, battles, and legacy.